My childhood was a long hallway hung with the sounds of choral and symphonic music.

Before I was older and could participate in ensembles, I was left to amuse myself in the vicinity of rehearsals; I would draw little characters on yellow legal pads while a live soundtrack of Tom Fettke pieces and Camp Kirkland arrangements washed over me from the next room. After that, high school band was the crucible of my education. Punctuated with amounts of Pink Floyd, Five Iron Frenzy, Caedmon’s Call, and the Goo Goo Dolls (judge not, lest ye pop the black balloon), I played my way through the annals of Percy Grainger, Clifton Williams, and Charles Ives. It comes as no surprise to me then, that I should still be following the career of one of my favorite choral and orchestral composers: Eric Whitacre.

Sometime early in my college years, our professor and band director trotted out a couple of Whitacre pieces called “Ghost Train” and “Sleep.” Both leaned well into program music, that sort of instrumental composition that conveys a more definitive narrative structure. “Ghost Train” sounded exactly how one might imagine a piece with that title to sound, full of rhythmic, driving cluster chords and ethereal whistles. “Sleep” though, at least for me, was transcendent.

It started out as a setting of Robert Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.” One of the most recognizable American poems—and arguably one of the best—the four-stanza work was, according to Whitacre, part of an earlier, surprise release of copyrights from the Frost estate. Other people had written settings of the work and, on his website, Whitacre admits to following a natural assumption that the poem was open for anyone’s use. For whatever reason though, the estate had then either closed or failed to renew the copyright. Undaunted, Whitacre contacted a poet friend, Charles Anthony Silvestri, to craft a poem correspondent to the meter and rhythm of Frost’s seminal work. The task seems almost ludicrous in its immensity now, but Silvestri turned out something (the next day!) that not only was appreciably Frostian, but also stood on its own:

The evening hangs beneath the moon,

A silver thread on darkened dune.

With closing eyes and resting head

I know that sleep is coming soon.

The result defies the psychology of overplaying. It doesn’t matter how many times I listen to it; the descending pattern of secundal suspensions and resolutions always raises goosebumps. The first time I heard it, of course, it wasn’t even the choral setting. Euphonium in my lap, I sat in the back of the capacious college band room hung with orange acoustic treatments like failed modern art. Our first few run-throughs—frankly, many of our run-throughs—were impressively bad. We were learning to be adult musicians, figuring out how to listen to one another and work as a creative team. Still, even with me harrumphing my way through half notes, the ethos of the piece shone through. Somebody in our little circle told me it was originally a choral piece, and I went hunting for a recording.

Despite the widespread, tacit notion that Beatlemania and movements of its ilk are limited to variants of the rock genre, cults of personality have often developed around composers and conductors in choral, symphonic, and jazz circles. Whitacre is no exception.

Internet searches—at that Cretaceous time around the year 2003—revealed little about Whitacre. His image, if you can call it that, graced the cover of an album called BCM...Saves the World. Whitacre and fellow composers Steven Bryant, Jim Bonney, and Jonathan Newman had created a loose conglomerate amongst themselves with the goal of liberating high school and college bands from the overgrazed pastures of more traditional wind ensemble works. In keeping with their unconventional musical wisdom, the album art has them drawn like hero characters out of Neon Genesis Evangelion. It was certainly a departure from the cut-and-dry Deutsche Grammaphon covers that populated the college music library.

Wait, wait, I hear you saying. Popular music is about what’s at Bonnaroo and Coachella; it’s about backbeats and the like. The closest we should ever get to a choir is The Oh Hellos. That’s fine; I’m not here to convince you otherwise. If we’re talking strictly about popularity, though, that’s something else. Despite the widespread, tacit notion that Beatlemania and movements of its ilk are limited to variants of the rock genre, cults of personality have often developed around composers and conductors in choral, symphonic, and jazz circles. Whitacre is no exception.

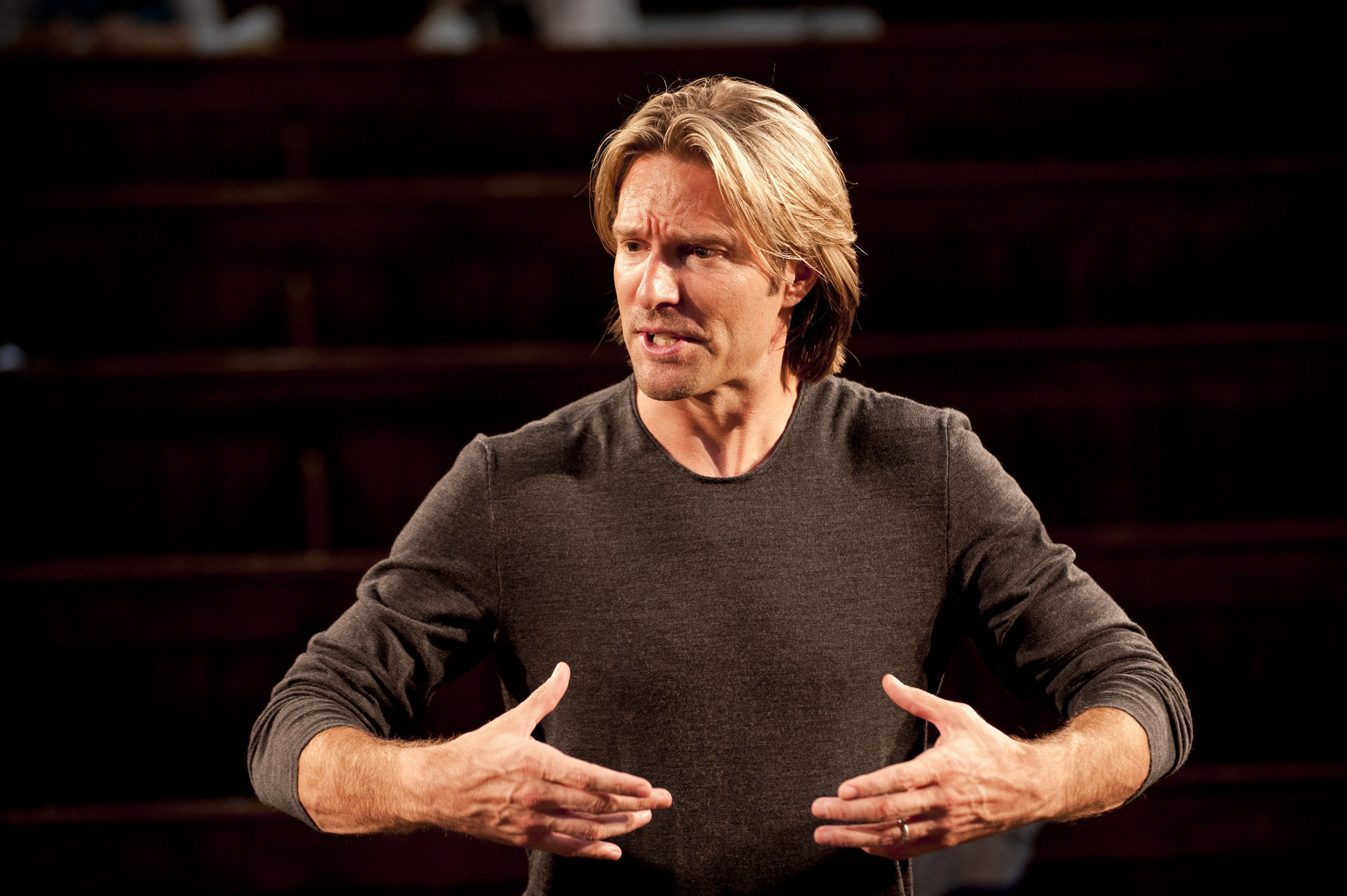

The man looks like a certifiable rock star: winning smile, svelte physique, and luscious hair that would make the corpse of Franz Liszt sit up and applaud. Actually, when you Google Whitacre’s image, the first tab that comes up is ‘hair,’ but we’ll let that be. The man conducts with a pensive, emotive brand of manual and facial choreography that perfectly translates his style of composition. Plus, he wields a modern technological savvy that has garnered him a much wider following and appreciation.

After seeing a video of a bold young fan soloing her way through “Sleep” on YouTube, Whitacre put together what he termed the Virtual Choir, for which participants followed instructions and sent in video recordings of themselves singing the parts of one of Whitacre’s choral pieces. For “Sleep” itself, the project consisted of two-thousand-plus people from fifty-eight countries. All of this got compiled by the Whitacre team with some digital conjuring (and presumably, an obtuse amount of real-time audio processing) and posted on the internet as a well-executed piece of global-communal art. The lyrics shine, which is astounding given the number of singers and given the amount of layered polyphonic material:

If there are noises in the night,

A frightening shadow, flickering light;

Then I surrender unto sleep,

Where clouds of dream give second sight.

Myself, I consider it something of a wonder that Whitacre hasn’t been staged at Big Ears or some such festival. His work certainly falls in line with some of the fringe elements commonly found at the Knoxville-based festival. Outside of “Sleep” and other works by his friend Silvestri, Whitacre tends to favor lyrics by E. E. Cummings and the celebrated Mexican diplomat and malcontent Octavio Paz. The latter’s poem “El cántaro roto” (along with a little bit of “Agua nocturna”) became the text for Whitacre’s piece “Cloudburst,” which features more vocal tone clusters, plus spoken word, hidden handbells, and the choir doing that snapping-clapping thing we all did at summer camp to create a rainstorm sound.

Hay que dormir con los ojos abiertos,

hay que soñar con les manos,

soñemos sueños activos de río buscando su cauce,

sueños de sol soñando sus mundos

(We must sleep with open eyes,

we must dream with our hands,

we must dream the dreams of a river seeking its course,

of the sun dreaming its worlds)

It is perhaps valuable in the throes of our current American culture for people to consider exquisite music by a white Nevadan containing lyrics by a late Mexican semi-socialist and statesman. In short, “Cloudburst” was important music ever since it was first written; now it is important for a whole new reason.

Choral music is normally separate from the centripetal upheaval of popular American tunes. Few people talking at the water cooler the week after the Grammys are concerned with anything outside of the Pop, R&B, Country, and Rock fields (who knew that Randy Newman won a Grammy last year!). As such, the standout choral or instrumental pieces take a little longer to rise to the top. We’re all familiar with Gershwin, Holst, and Handel, but most of our brains go fuzzy after Duke Ellington. For those paying attention to such things, though, Eric Whitacre is the cream of the new crop. For the wider audience—for anyone whose emotions are brought to the forefront by music—he is most certainly worthy of an uninterrupted listen. But take care; he might open your ears to a world of delight that never made the pop charts.