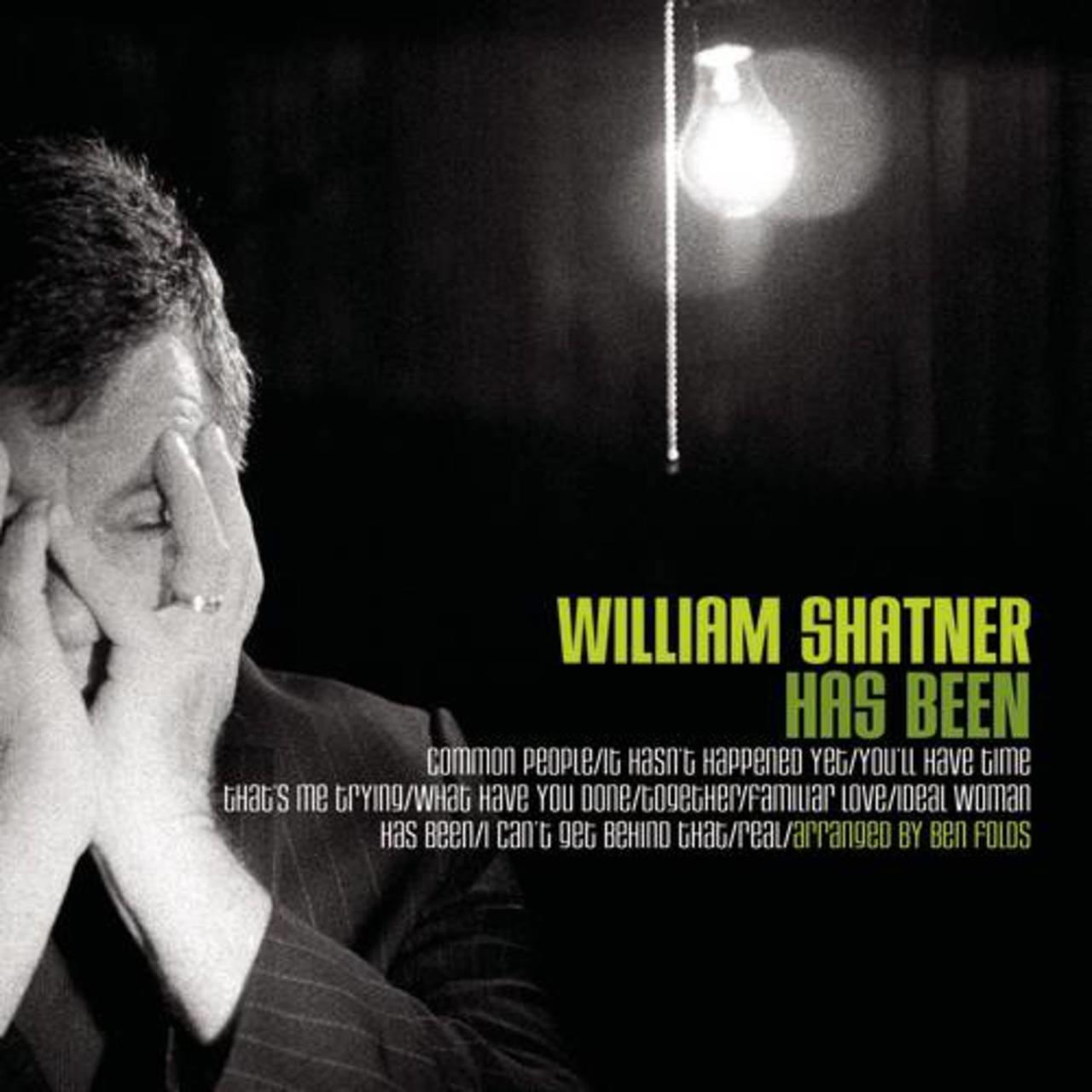

William Shatner’s album Has Been came out on Shout! Factory in 2004, and I’ve never had the heart to get rid of it.

At the very least, it begs repeated curiosity over its indefinability. At most, it appeals to my love of poetry. I only knew Shatner from the show Rescue 911 and as a legend from my dad’s love of Star Trek. By the time I encountered the man on prime time, Captain Picard already helmed the Enterprise, and Shatner seemed possessed of a permanent sardonicism as he tried to escape the clutches of Captain James T. Kirk.

Has Been was his third album. The first had been a mashup of Shakespeare, Cyrano de Bergerac, and popular tunes of the time, and it seemed to live at the Will Ferrell-like intersection of uncomfortable comedy that looked like extreme sobriety. The second was a live recording of a one-man show, in which he notedly returned to the character of Cyrano. Both albums lean out into “space, the final frontier,” sporting cosmically-themed graphics or tracks. Their existence and bent beg the question of what the man himself was or might have been without his seminal television and film character. How much of Kirk was Shatner, and how much of Shatner couldn’t help but be Kirk?

Shatner’s career after Star Trek resembled a glass house around the man’s psyche, as he wrestled with the weight of his gravitas through spoofs and interviews and found other outlets for his creativity. Has Been charts a point in the actor’s life when he seemed comfortable with having that 800-pound sci-fi gorilla in the room. Aside from a couple classy, vulnerable nods in the direction of his early career, much of the spoken-word music deals with other things.

Shatner gets tongue-in-cheek about the strange animal of his celebrity, opening with the proletarian jab of “Common People” by Pulp and taking on the ghosts of his detractors in the title track, which is a Spaghetti Western anthem.

Let’s stop there a moment, because we just crossed into uncharted territory. How can Britpop and a track worthy of Sergio Leone make good bedfellows? The record is produced by Ben Folds, and it feels like a fairly pure collaboration, a John-and-Paul style combo that’s hard to recreate. Folds lives at the well-woven center of his many musical threads, reaching into jazz, country, avant-garde, and even minimalism. A Who’s Who of musicians brings the vision to life, including Adrian Belew, Fleming and John, Aimee Mann, Jon Auer of The Posies, and Brad Paisley. In the final analysis, Folds himself is the cohesive musical element, applying his production style and instrumental chops across multiple genres. The result is somewhat episodic at points, but that works in the record’s favor.

By the second track though, we know we’re out beyond the tropes of Shatner as a byword among critics. “It Hasn’t Happened Yet” assesses the normal midlife crisis of living between the shadow of mortality and a curriculum vitae that, in the long history of the world, doesn’t amount to much.

People come up and say hello

Okay, I can get to the front of the line

But you have to ignore the looks

and yet

I’m waiting for that feeling of contentment

That ease at night when you put your head down

and the rhythms slow to sleep…

At my age I need serenity

I need peace

It hasn’t happened yet

It makes for good medicine, especially as Shatner seems to give priority to making good art rather than pleasing a nebulous panel of imagined critics.

That’s not to say the entire album is emotionally leaden. The comedic shenanigans—which still carry a goodly amount of introspection—begin with the third track, “You’ll Have Time.”

Live life

Live life

Like you’re gonna die

…because you’re gonna

The song has the brilliant dark humor to be a slow-burn gospel piece, replete with a choir backup and Ben Folds playing what certain congregations might call preachin’ chords on a lo-fi Wurlitzer. It’s brazen and wonderful and builds to the choir reciting multiple means of shuffling off the mortal coil, including “choke on a chicken bone.” “Am I gonna die?” sings a choir member. “You are gonna die,” Shatner reassures her.

The comedy reaches a fever pitch with the tune “I Can’t Get Behind That,” in which Shatner and Henry Rollins rant back and forth about things that annoy them (and probably us, too), while Matt Chamberlain goes bananas on a drum kit and Adrian Belew makes sound effects and racket on an electric. It’s like a scene from Birdman, turned up to eleven, especially with the drums. You can almost see the two vocalists in a studio, waving their arms at each other, having a Nicolas Cage-style breakdown.

Has Been also contains moments of incredible intimacy. On “What Have You Done,” Shatner walks us through the heart-scalding moment of arriving home one night to find his third wife, Nerine, drowned in their pool out back. It’s an instance in which, like a crucifixion painting, the sheer weight of the backstory becomes, in large part, the weight of the work. It almost resists critical approach. Shatner couches the poem in the minimalist undercurrent of Sebastian Steinberg’s bowed upright bass overtones. The noise is just present enough to lend a dark tension, and knowledge of the context makes listening to the piece difficult.

As a personal journal, the lyricism hits hard, even uncomfortably so. On “Familiar Love,” Shatner and Folds explore the physical and erotic territory of a longstanding relationship. Listening can feel voyeuristic here, but there’s also something so wonderfully plain about the poem. Its sensuality lacks the heady desperation and idealization of most Hollywood sexual narrative. It even wanders away from the bed into the curious moments of prismatic normalcy that only occur in lengthy relationships.

Its sensuality lacks the heady desperation and idealization of most of Hollywood's sexual narratives.

Sliced apples, almond butter

and feta cheese

Let’s feed the dogs

Send out for Chinese

Watching movies on TV and fall asleep

Arms wrapped around

So happy

We weep

The people are normal people, a fact reinforced in the follow-up track called “Ideal Woman,” in which Shatner pokes fun at his own lingering sense of entitlement within the relationship.

It’s you I fell in love with Your turn of phrase

Your sensitivity

Your irrational moods

Well, maybe that could go

But everything else I want you to be you

Most people probably don’t go in for William Shatner as a musical poet, it’s true, but this album deserves a broad audience and critical attention as a serious work. It isn’t divorced from the theatrical tonnage of Shatner’s characteristic delivery and performance history, and that’s on purpose. Instead, the record plays into his charisma and couples it with a fierce humanity that might just awaken your empathy as a listener, even while it lets you know that William Shatner has some empathy for you.