An acquaintance once told me, “John Prine is my favorite poet.” We became instant friends and talked for hours.

To listen to Prine’s music—to hear his stories of ordinary people like Donald and Lydia, going steady with Iron Ore Betty, writing letters to Dear Abby, and the shrapnel in Sam Stone’s knee—evokes the feeling of a conversation with an old friend. It’s like talking with someone who has secrets they're willing to pour out to you, all tales that will make you cackle with laughter or get down on your knees in sorrow.

The morning after Prine sipped his last breath through a ventilator, one of the thousands losing their lives to COVID-19, to sort through my own emotions, I wrote a personal tribute to this beloved singer-songwriter. My heart is both broken he is gone and relieved that he is not suffering. The heartbreak is because John has been a good, good friend throughout the years. He sung the emotions for which I might never have found words. He made me laugh and cry, stop and think. He has been real, so real, and his loss leaves a big hole in the world.

Since last night I’ve been listening to his albums one by one—really, I’ve been listening to him and Bill Withers for days—but the one song that stood out to me this morning was “Please Don’t Bury Me.”

Please don’t bury me down in the cold, cold ground.

No, I’m gonna have ’em cut me up and pass me all around.

In a way, John Prine did that throughout his career of making music. He has left us with so many pieces of him, pieces that can never fall prey to the brevity of life.

In a way, John Prine did that throughout his career of making music. He has left us with so many pieces of him, pieces that can never fall prey to the brevity of life.

From 1971 to 2018, Prine released 25 albums and performed countless shows. He has sung with more artists than I can imagine and his songs have been recorded by everyone from Carl Perkins to Bette Midler, Johnny Cash to Joan Baez, 10,000 Maniacs to Don Williams. One of the best-known covers of his work was Bonnie Raitt’s “Angel from Montgomery.” Prine is one of a group of singers and songwriters I love whose music never really fit—or tried to fit, for that matter—in a single genre. He has recorded songs labeled country, blues, folk, rock, and some variation of them all.

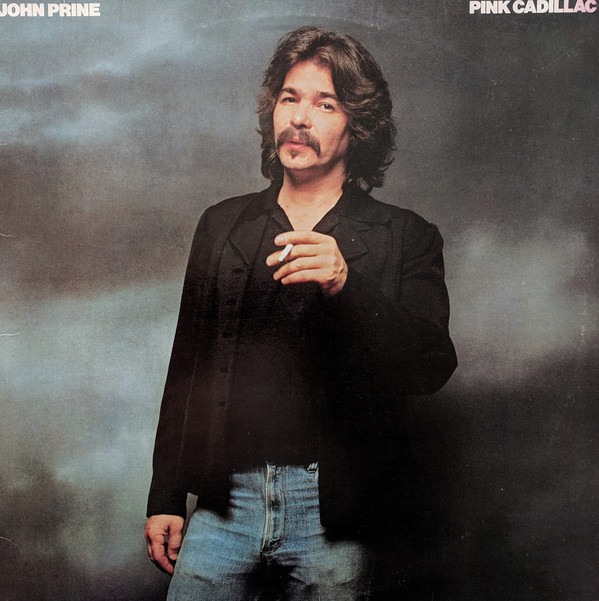

Some of his most far-reaching recordings were from my least favorite (and the worst-reviewed) of his albums, Pink Cadillac, which came out in 1979. “Ubangi Stomp” (written by Charles Underwood) has the beat of an Elvis tune, and “Killing the Blues” (written by Rowland Salley) sounded a lot better when Robert Plant and Allison Kraus recorded it. In his defense, Prine is first and foremost a songwriter, and he only wrote half the songs on Pink Cadillac before calling it quits one album later and starting his own label, Oh Boy Records.

No matter the label or the genre, though, Prine wrote and sang the songs of “the human condition.” I hear the truth of everyday people’s lives in songs like “Somewhere Someone’s Falling In Love” and lyrics like, “I threw a party and nobody came.” Even on Pink Cadillac, he recorded “How Lucky” and asked the ironic question, “How lucky can one man get?” Prine has said he started writing that song in the parking lot of an old haunt, a hot dog stand, and he would have finished but his radiator hose blew. See? He’s just a real guy who lived a real life! (He wrote about the radiator hose in “That’s The Way The World Goes Round".)

I’ll admit I didn’t discover John Prine in my youth. I grew up in a time and in a place where there was a lot of talk of “the devil’s music,” and I myself was doing a lot of Bible reading to avoid the slow-death boredom of riding in a car from one end of a tiny rural town to the other. When I was bobbing my head listening to my first Prine song, a duet with Iris Dement called “In Spite of Ourselves,” I figured out pretty quickly why I’d not heard Prine’s music in those early years. I could only imagine how horrified my mother would have been if I had run around singing lyrics like, “She gets it on like the Easter bunny!” That early naivete is likely why I didn’t catch on to the underlying story of Prine’s “Illegal Smile” for a while as well!

And you may see me tonight with an illegal smile

It don’t cost very much, but it lasts a long while

Hearing “In Spite of Ourselves” was just the opening of a door for me, not just to horny or corny lyrics that made me laugh, but to the landscape of the world and the trials of its people. Over the years, I’ve understood others and even myself so much better through the lens of a John Prine song.

As a former journalist, I’ve always been nosey. I often tell people I came out of the womb asking questions, and I must have come out eavesdropping on other people’s conversations, too, because I love to do that. When I heard “Living in the Future,” I was sure that Prine wrote the song after listening to people in a soup line telling big stories about everything they knew, without a doubt, was going to happen in the world. It turns out that he wrote the story in response to reading stories in Parade magazine year after year about what the future would look like in cities around the globe. He said it pretty plainly:

We are living in the future

I’ll tell you how I know

I read it in the paper

Fifteen years ago

This experience reminded me that one of the reasons those people in the imaginary soup lines of Prine’s song were know-it-alls was because they saw things through their own lens. Just like I did.

It wasn’t the last time I saw my own shortcomings in a Prine song. He has penned so many words I was missing for my feelings. A most recent example came while talking with a friend who was feeling down. I felt such deep empathy, but couldn’t find the words to say I was worried. Instead, I sent some words from Prine:

I hear a lot of empty spaces

I see a big hole in you

I feel an outline that traces

An imaginary path back to you

This ain’t no ordinary blue

“No Ordinary Blue” was from Prine’s final album, Tree of Forgiveness, released in 2018. It was the only album to make it to the top 5 on the Billboard charts. The day it was released, I remember listening to every word while riding on a train between The Hague and Delft. Tears filled my eyes as I thought there was so much about the album that sounded like his way of saying goodbye. He had already battled and won against cancer twice, and his age was creeping higher. Of course, as I look back, John Prine, true to the Kentucky roots of his parents, had been singing about death for a long time.

Since his death “When I Get to Heaven” has been shared far and wide on social media, with memes highlighting Prine’s opening spoken lyrics.

When I get to heaven, I’m gonna shake God’s hand

Thank him for more blessings than one man can stand

Then I’m gonna get a guitar and start a rock-n-roll band

Check into a swell hotel; ain’t the afterlife grand?

Yet as early as his first album, released in 1971, Prine was singing about his last days in “Paradise.”

When I die let my ashes float down the Green River

Let my soul roll on up to the Rochester dam

It seems to me that John felt the fortune of his life deeply, the misfortune of others just as sincerely, and that he knew for a long time his last day would come. We just didn’t know it would hurt so much. Wherever your ashes float, wherever you start your next rock-n-roll band, please know, dear John, we will be listening.