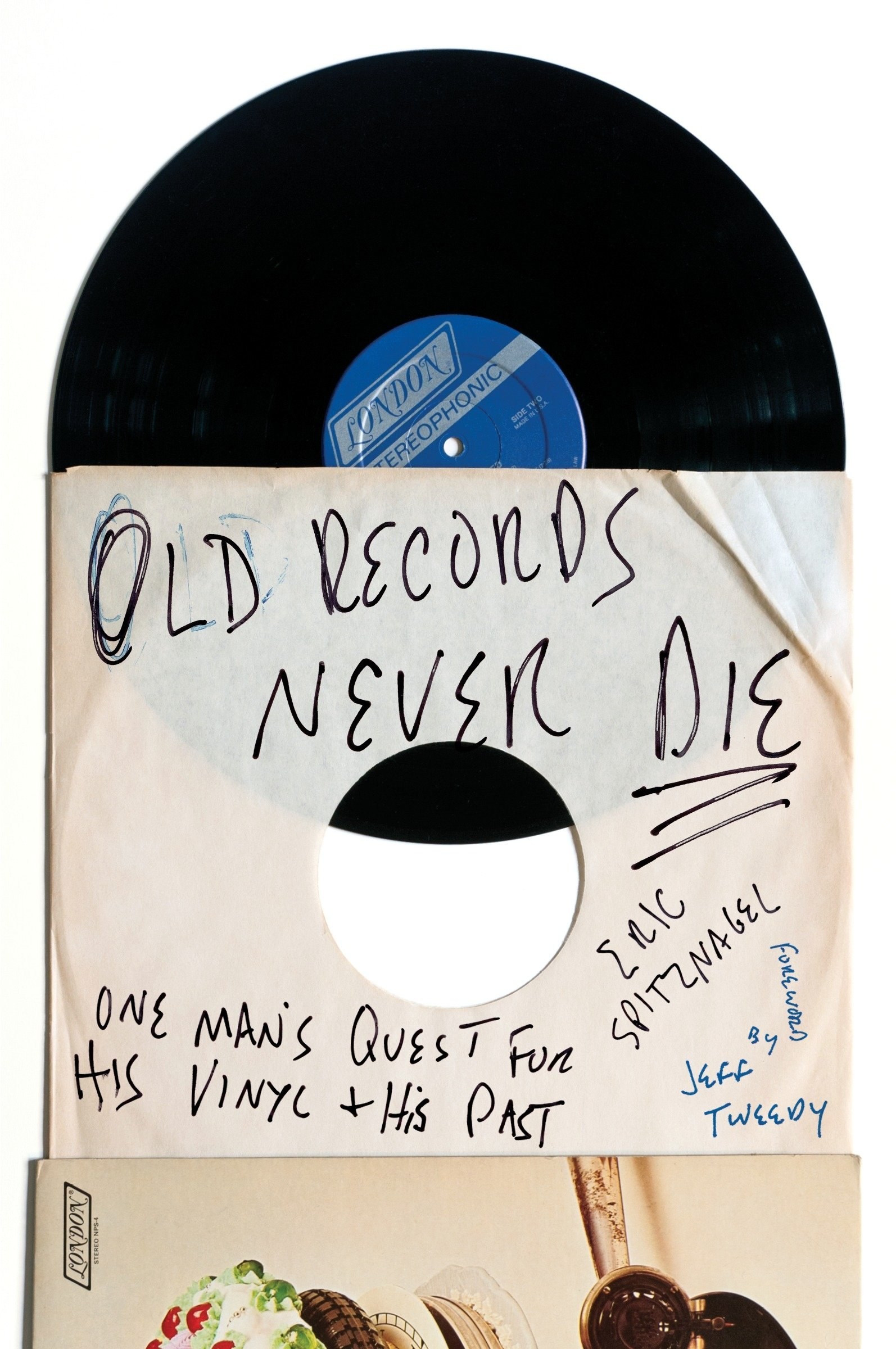

Entertainment journalist Eric Spitznagel was in the middle of conducting an interview for MTV Hive when it finally dawned on him what he had lost when he sold off his record collection years before.

Who more appropriate to awaken him to the realization than Questlove, a man whose own storied vinyl stockpile is said to number over 70,000? This minor moment of heartbreak is also one of the more amusing passages in Spitznagel’s memoir, Old Records Never Die:

“I’ve always taken meticulous care of that stuff,” he told me. “I’ve always had some sort of library system for my records, so nothing just disappeared without me knowing about it. Not just ‘Rapper’s Delight,’ but all my records. They’ve never been in any danger. You’re probably the same way about your records.”

I was silent for a second.

“I don’t have records anymore,” I told him. “I sold them all long ago.”

Now there was silence on the other end of the phone.

“Oh, man, I’m sorry,” Quest finally said, his voice a whisper.

It was this conversation that spurred Spitznagel on a journey to recover the old records that he sold off for subsistence in the lean years of young adulthood. If that sounds doable enough, the catch makes it seemingly impossible: he has to track down the actual records that were once his own. The new reissue of Pixies’ Doolittle that he buys at Reckless Records in Chicago where he lives isn’t good enough. “It looked like something that used to be meaningful to me,” Spitznagel writes, “but it was just a carbon copy...I wanted my records. My exact records.”

Perhaps recognizing the cost, time and effort that getting back every last one would take, shortly into his quest he sits in a Chinese restaurant and makes a short list of the LPs that he’d be able to recognize for certain: Liz Phair’s Exile in Guyville, Rolling Stones’ Let it Bleed, Band on the Run, Rain Dogs, New York Dolls, and so on. In a metropolitan area as populated as Chicago, finding any of your own needles in the public haystack seems an impossible task, not to mention that they could have traveled well beyond state lines after all that time. Then, the impossible happens at the Chicagoland Record Collectors Show in the Hillside suburb of the city. There, in a box of 50-cent castaways, against all odds, is his old copy of Bon Jovi’s Slippery When Wet.

Spitznagel is sure it’s his because of the phone number written on the front of it, and when he eventually meets up with an old girlfriend, Heather, she confirms it is in fact her old number. He actually found one, which in itself is enough of a miracle to keep the reader invested in Spitznagel’s search throughout the rest of the book. But then he manages to track down another one, and you start to wonder: if he can find his old copies of Slippery When Wet and Let It Bleed after all these years, maybe I could find a few of my old records, too...

Tim Burgess, frontman for the Charlatans (or the Charlatans UK, as they’ve had to be known in the US), does not need to go out and find his old records. He hasn’t been as obsessive as Questlove with his cataloging system, but selling his library off is probably something that has never crossed his mind. Many albums in his collection have come and gone over the years as he’s loaned them out or given them away, but that’s the way he likes it, and he is happy to keep buying copies of his favorite records as they come and go.

The conceit of Burgess’ second book, punningly titled Tim Book Two, is explained in the opening pages:

“I’ve always thought that I was defined by records. Not just ones I’ve been involved in recording but every one I’ve ever loved, bought, fallen out of love with or that has soundtracked a particular chapter of my life. They are like punctuation marks. If I need to think back to an event in my life, it’s easiest to do it with singles and albums.”

Spitznagel’s concern, as he was living out the events that drive the narrative of his book, is much more urgent than my own. Nonetheless, every once in a while, I will go online and reclaim a CD or two that should never have been set free.

Burgess could have easily decided to pick 20 or 30 of his favorite albums and write essays about what they mean to him. Instead, he chooses a more original plot. Having already written a memoir, Telling Stories, he turns Tim Book Two into an international scavenger hunt fueled by recommendations from a number of friends -- mostly celebrities from the worlds of music, film and television. Each section, at some point, provides the story of how the recommendation came about, sometimes including transcripts of the recommender’s own emails or text messages. Around that, Burgess recounts how and where he tracks down said album, even the particular experiences in each record store; interesting finds from digging through the bins, conversations with shop owners and other interactions.

Among the surprise recommendations are an early Hüsker Dü record picked by Chan Marshall of Cat Power, and Carl Barât of the Libertines suggesting the first Rage Against the Machine album instead of, you know, Is This It. On the other end of the spectrum, David Lynch is almost painfully on-brand with his choice of Captain Beefheart’s Trout Mask Replica. Notorious perfectionist Kevin Shields of My Bloody Valentine recommends, naturally, Pet Sounds. This selection leads Burgess to recall a great on-point anecdote about Shields listening to all 200 promo cassettes of Loveless before they were sent out in advance of the album’s release.

The book still qualifies as a kind of memoir, dotted as it is with anecdotes from Burgess’ past experiences, but its focus is more on the recent past, present and future of some of the author’s ongoing concerns: his band, the fate of record stores, where his next cup of coffee is coming from. Yet, in seeking out these records that have been so important to his friends, Burgess is giving a glimpse into the stories of their lives in vinyl, as well. Books such as Brett Milano’s Vinyl Junkies, Amanda Petrusich’s Do Not Sell At Any Price, and Elion Paz’s Dust & Grooves, have already delved into the lives of dedicated record collectors. Spitznagel and Burgess offer a similar but different genre, the ‘memoir in vinyl.’

The records themselves are important, the music they contain undoubtedly so, but the wax that Spitznagel and Burgess wax rhapsodic about has that deeper meaning of having served as signposts and mile markers in someone’s life. Mint condition doesn’t necessarily give them value (though Burgess makes note of his preference for original pressings), it is what they mean personally to the owner that does. The determination of serious collectors to spare no expense tracking down a one-of-a-kind original may inspire awe in some, but the warm feeling of reconnecting with a record that you held dear in high school, even a beat-up copy, is a little more relatable. At one point, Spitznagel thinks he might have found his Rosebud, the copy of the Replacements’ Let It Be that he used to stash his weed in, but, alas, the skip on “Androgynous” is in the wrong place.

Yet, in seeking out these records that have been so important to his friends, Burgess is giving a glimpse into the stories of their lives in vinyl, as well.

The way he describes the familiarity of scars on one’s own records rings true. Personally speaking, whenever I hear Joy Division’s “Isolation”, I always anticipate the skip that’s on the copy of Closer I got for five bucks at Second Time Around in the U-District of Seattle back in 1994. That said, having served my teenage time in the 1990s, I just missed the boat on growing up with the same kind of intense attachment to vinyl that Burgess, Spitznagel, and so many others of their generation (and previous generations) have. My first record was a 7” single, but the next four or so albums I got after that were cassette tapes. I understood what Eddie Vedder meant when he said something to the effect of “you can’t hug a CD”, but I still bought Vitalogy on compact disc because it was cheaper and that’s how most everyone else bought it, too.

My humble vinyl collection came together in that decade mostly by way of three factors: indie rock and Britpop 7” singles, used records that were cheaper than CDs, or an album I wanted on a given day in a given store was somehow only available on vinyl. The last of those factors was how I unintentionally came to own Catherine Wheel’s Happy Days, probably the third-best Catherine Wheel album, on transparent double vinyl. This is also the reason why I have Creeper Lagoon’s I Become Small and Go, Clikatat Ikatowi’s River of Souls, and a promo copy Happy Mondays’ Bummed on 12”. Nowadays, I feel pretty lucky to own some of the things I have from that era on vinyl, but the accumulation of it was almost entirely incidental.

Having only a few handfuls of vinyl throughout my twenties, it also fortunately never occurred to me to sell any of it off. Spitznagel’s situation, however, is still very relatable. At least once a week I walk over to my CD shelf and look for something that should be there, but isn’t. Some were misplaced or broken in one of a few long-distance moves, and others -- as with many of Burgess’ favorite records -- were loaned out to friends without return. That’s life.

A decent chunk of the collection, though, was sold off bit-by-bit in the early 2000s, while working only part time in college, in order to trade for new CDs. That was a choice, but we all know it was a different situation back then. I only ever had the slowest internet connection available (if I had one at all), so trying to use Napster or Limewire would have taken hours if not days, and Spotify wasn’t around until the end of that decade.

Spitznagel’s concern, as he was living out the events that drive the narrative of his book, is much more urgent than my own. Nonetheless, every once in a while, I will go online and reclaim a CD or two that should never have been set free. The format gets less love these days than 8-track, but it’s what the vast majority of my collection was made of. Obviously, they don’t have to be my own original copies, and I draw the price line well before, say, the $69.99 that Burgess spends on a copy of White Zombie’s Soul-Crusher at the recommendation of Iggy Pop. Still, there is one old EP out there that I wonder if I could, by some freak chance, get my own copy of back: one of a limited edition of 500, which now sells for as much as $40 when it pops up on Discogs.

Whenever the urge comes to pull the trigger on purchasing that EP, a question at the heart of Spitznagel’s book flashes like a red light. Is it really possible to reclaim a part of yourself through the possession of an object from your past? If I buy that out-of-print, self-released debut from that old local dream pop group for a mere $7 (even though my original copy was a dollar bin rescue), what missing piece of my former self might really be restored? It was short-sighted to cast off Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci’s Bwyd Time and Heavy Stereo’s Deja Voodoo, but surely not all of those obscure 1990s albums can be talismans of youth. If they can be, it’s going to start adding up.

Gathering vinyl these days, a dinged up old slab off wax with its own life story has as much allure to me as something new. A record with a history behind it, even one that isn’t shared with your own, has a different kind of value -- especially for those who like the smell of damp basement-aged cardboard. As a parent on a budget looking to justify acquiring outdated media, rarity is of little allure from a buying perspective. Who cares about a record no one has heard of that you can hardly take out of the sleeve for fear of dropping its market value? Finding that copy of Frampton Comes Alive! for a dollar means getting to claim a tiny piece of populist history, even if you weren’t actually alive yourself when it happened.

After one of his Tim Peaks festivals on the Isle of Wight, Burgess reached out to Oxfam for record donations. He recalls finding in one box sent by the charity shop “...a rare Beatles release in mono”, but the previous owner, Clarke, had written his name on the front, which chopped the value down to a fraction of the £2,000 a clean copy would fetch. “Ah well,” Burgess concedes, “that’s the thing about records -- they’re living, breathing things.” They are indeed, and if Desmond helped keep the price down on the copy of the Band’s Music from Big Pink that I picked up over the holidays by writing his name on the back, then that’s all the better.