The Wikipedia page for “1999 Christmas albums” reads like the guest list for a White House Christmas gala:

Tricia Yearwood, Garth Brooks, Kenny G, Amy Grant, 98 Degrees, Jewel, Fourplay, The Irish Rovers, Reba McEntire, Ringo Starr.

All of these artists unleashed CD-shaped parcels of adult contemporary Christmas cheer on the world. There’s enough music on those albums to fill any holiday party, but, what the hell, we might as well get one more--how about Mr. Hankey’s Christmas Classics, South Park’s contribution to the Christmas canon? All of this and Y2K? Christmas really is magical.

Maybe this surfeit of Christmas albums was related to the impending millennial ball drop, or maybe Christmas 1999 was an especially celebratory season. After all, this was the year Prince had been amping us up for since 1982: party over, oops, out of time. But, most likely, it was because Christmas albums are easy to record and even easier to sell, and 1999 was a good year for major labels to turn Christmas revelry into cold cash.

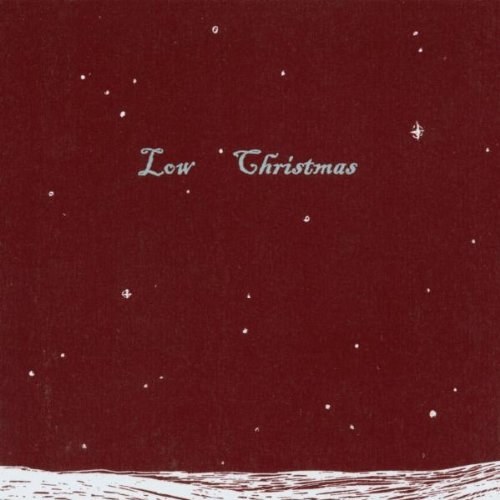

Buried in the slush pile of records from Spanish tenors such as Placido Domingo and blue-collar comedians such as Bill Engvall, a trio from Duluth, Minnesota quietly released a bare-bones Christmas record to their fans 20 years ago this November. Christmas, an eight-song EP by Low, is sonically, lyrically, and thematically a direct opposite of all the bloated, over-produced major label records released that year.

The EP is skeletal with a backbone of no more than four instruments—bass, guitar, drums, maybe some keys or extra percussion—on any given track. The album candidly met the general excess of the Christmas season head-on and refused to be blown over by the saccharine sentiment and musical overindulgence of Christmas records released the same year—records with at least 10 times the band’s budget. Like David prepping his sling to take down Goliath, Christmas doesn’t try to overpower with volume or force; it sticks to the same, steadfast musical formula that Low has always employed: slow and quiet, dark yet sincere.

Released in November, 1999, on the heels of their Steve Albini-produced Secret Name, Low was on the cusp of expanding their indie audience beyond Midwestern circles. Secret Name was the band’s first full-length LP for the indie label Kranky and it had a marquee-level producer . Albini helped broaden and tighten their metallic guitars and made the minimalist drums sound warm and hollow at the same time. There were even hints of a playful side to the band on “2-Step” and “Missouri.” By the time Secret Name was released, Low had their musical aesthetic nailed down and Secret Name felt like the first time the music was allowed to breathe, to expand across boundaries. There was a sense that whatever came next would only lift Low upward.

Their next proper full-length, Things We Lost In the Fire, achieved that—it’s probably the record most Low fans will point to as their best—but before the fire was the snow. Christmas was the breather that the band needed; a reset to their senses that demonstrated their musical inscrutability.

Christmas is as beloved and appreciated as any release in the band's enormous—and still growing—catalog. A Christmas record from Low makes total sense artistically and thematically, even though it made zero sense commercially. Christmas is tailored to reflect the difficult emotional landscape of the holidays. Chill and warmth, snow and slush, sadness and hope coupled against loneliness and missing family members. Despite the perception, the holidays aren’t all good cheer and they definitely aren’t a 1999-level of indie cool. But Christmas gave some credibility to the season, even if listeners didn’t exactly know it would last a few decades more.

Beginning with the time that Bing Crosby first shuffled up to a microphone, most of the music we ingest every December is trite, maudlin, and dripping with Boomer nostalgia. At its best, Christmas music is catchy and inoffensive; at its worst, it’s insincere and wholly devoted to the seasonal worship of the Almighty dollar. Low bucked that trend and recorded their EP solely for the sake of the season, with hardly a thought given to album sales. It was an odd move for a band with only a half-decade under their belts, but it’s the kind of maneuver that makes the band so well-respected and beloved among fans.

Like Sisyphus cresting the hilltop wiping the sweat from his brow, this little EP broke through all the noise and the static.

Yet somehow, a small Christmas miracle happened. Like Sisyphus cresting the hilltop wiping the sweat from his brow, this little EP broke through all the noise and the static. Slowly, of course, because, just like Low’s decade-spanning career, slow and steady is the only setting on the band's throttle. Thanks in large part to John Peel featuring the record on his BBC show, Christmas found an audience, one comprised of listeners that embraced the cruel ambivalence of the season and longed for some music that reflected such a reality back. It’s a holiday record that acknowledged its audience’s context and addressed them with integrity.

Christmas contains a few of Low’s most upbeat and joyous recordings. Opener “Just Like Christmas” is a European romp via sleigh ride from Stockholm to Oslo, complete with sleigh bells and a hoof-beat drum pattern that creeps oh-so-close to a shuffle. “And you said it was like Christmas / but you were wrong / it wasn’t like Christmas at all,” Mimi Parker chides in the opening verse, right before an about-face brings the song to an awareness, “But we felt so young / It was just like Christmas.”

Though more than half of the songs are original Christmas songs—a characteristic of very few Christmas records—not even Low could pass up an opportunity to record a handful of Christmas covers. While “Silent Night” is perfectly lovely and shows off the vocal harmonies of Alan Sparhawk and Parker, an underplayed element of Low’s chemistry, it stills sounds exactly as it should. “Blue Christmas” is a bit of a curveball as it is perhaps the only time Low attempted a song with a mild country swing, while “Little Drummer Boy” was so magnetically strange and lovely that The Gap licensed it for use in a 60-second spot for the Christmas season of 2000.

“Little Drummer Boy,” though, is the best approximation of how Low takes tradition and folds it in on itself to meet their vision. The drums, an element so prominent it appears in the title of the song, are nearly non-existent. Instead, they are replaced with a curtain of white noise and ambient drone that would make Brian Eno swoon. It’s a jarring listen and it creates a physical chasm as your senses attempt to adjust to a flood of noise pouring forth. Soon enough the melody appears, however; those familiar “pa-rum-pum-pum-pum”s. Then the song settles in and a hypnotic wave washes over.

When I interviewed Sparhawk about the EP in 2015, he told me that the sound quality on “Little Drummer Boy” was a point of contention for some listeners. They thought it was unintentional. At the time we spoke, I was incredulous and thought, “There’s no way anyone ever thought that.” Then I heard “Quorum.” the opening track from 2018’s Double Negative, and the aural noise of “Little Drummer Boy” made sense again. The potency of noise and the shock of its arrival is a thread that Low have pulled through their career. Aurally complex, “Little Drummer Boy” is recognizable but not a safe interpretation of a song many of us know.

Here’s something you won’t hear often about Christmas albums: the original songs are the best ones on the record. The casual observances of “Taking Down the Tree,” the sharp-tongued observations of “If You Were Born Today,” or the sparse platitudes in “One Special Gift” are inarguably better than “Blue Christmas” or “Silent Night.”

Even if it’s broken and bittersweet, as the songs sometimes indicate, we still set the star at the highest peak on the tree, if only because it forces us to look up—past ourselves, past our foibles, past the humanism of this earth, toward something higher. Toward heaven, still.

For a season supposedly filled with so much hope and promise, Low draws out the inherent dread and anxiety that the season brings, but they also address those feelings with nothing but heart. The days leading up to Christmas may be filled with depression and literal darkness, chilly winds, and inches of snow, but Low is, if nothing else, a band pointedly connected to the human condition and all the flaws that come with it. In just under 30 minutes, we’re ushered from snow scenes of childlike joy to packing up the season, making a stop or two along the way to observe the plight of immigrants (“Long Way Around the Sea”) and turn in a cover of an Elvis Presley tune. “If you were born today / we’d kill you by age eight / never get the chance to say / joy to the world / and peace of earth,” Sparhawk sings. Is that what you’d expect from a Christmas album? If not, what should we expect from a song subtitled “(Song for the Little Baby Jesus).” “Away In a Manger,” it is not, but Low has never minced words—why would Christmas be any different?

Sparhawk and Parker have always been spent about their religious affiliation and beliefs in interviews and in their music. (Parker is a member of the Mormon LDS; Sparhawk is a convert.) They don’t explicitly allow their religion to dictate songwriting, but they don’t shy away from it either. Religious imagery in Low’s catalog is abundant, but Christmas is the first (and only) full song-cycle of the band that wipes away any doubt about their religious observances. Yet the songs still question and seek the significance of a holiday like Christmas amidst a culture of wealth and ego. If anything, Christmas occasionally leaves you wondering, “Well, do they like Christmas or not?” Ultimately, the answer, I believe, is yes.

That is the kind of thoughtful, lasting impact that Christmas provides, the kind that doesn’t offer quick, celebratory answers jammed into songs about reindeer, bows, and mistletoe kisses. “Seems before it's over / it’s begun,” Parker sings on “Taking Down the Tree.” Indeed. The season comes on like a rushing river and disappears before our eyes can adjust to its light. Even if it’s broken and bittersweet, as the songs sometimes indicate, we still set the star at the highest peak on the tree, if only because it forces us to look up—past ourselves, past our foibles, past the humanism of this earth, toward something higher. Toward heaven, still.