The goalposts have changed for Alec Ounsworth over the years.

Rather, Ounsworth has changed the goalposts. Eight albums into his career as front man for Clap Your Hands Say Yeah, Ounsworth says what began as a devotion to musical excellence has become a pursuit for meaningful connection. Yes the music still matters, but if it doesn't reach someone then something has gone wrong.

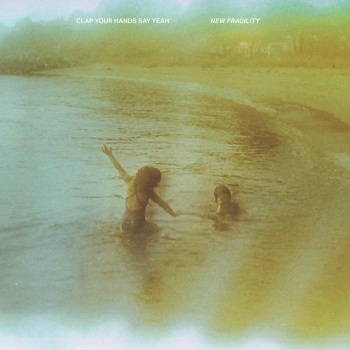

That shift explains much of Ounsworth's latest album, a brilliant release entitled New Fragility marked by personal, even vulnerable, tracks that allow the listener to connect in deeper ways with an artist who is trying his best to adapt admits change and retain hope amidst the cynicism.

We recently sat down with Ounsworth to hear more about his creative drive, why he never wanted to release his first album, and the pains of being unkind to himself.

Analogue: On the closing track to this new album, there’s this wonderful couplet I can’t get over where you say something like “I am not behind this door / I don’t live there anymore.” It feels like this great summary of New Fragility, which to me feels like an album you can’t make until you’ve been at this a long time. Does the new album feel that way to you?

Alec Ounsworth: A lot of people I admire have been going for a long time. I think they’re adapting and growing. It’s funny because people think when you’ve made a record a long time ago, whatever the public might perceive that it must begin and end there or something along those lines. My friends like Dave Bazan, Elvis Perkins, Will Johnson—guys like this I have a lot of respect for—are still going for at least as long as I’ve been going and they’re still putting out very interesting stuff.

I think they ignore the fact that the world is watching. That’s really the trick is to understand and have the confidence that you’re doing it because you believe in it above and beyond everything else. Then you hope and cross your fingers that you’ll connect with somebody else along those same lines.

As far as the lyric goes, on this album, there’s a lot of disenchantment, disillusion, and heartbreak in regards to the country. I’d like to also imagine there’s a sense of hope behind all of it, like I’m going to adapt to the circumstances given and I really hope the other side can do the same. That’s the idea moving forward.

"For example, my first album, I didn’t even want to release it. My mom was the one who said, ‘Just do it. See what happens.’ I’m not kidding."

It’s not easy, especially as most of these songs were written under the last administration. America has been trying my patience for a little while. [Laughs] I grew up in that environment, just questioning everything and it breeds a certain cynicism, but I’d like to think it’s not without its share of hope.

Analogue: Let me ask about that prompt. Is that for the sake of the listener?

Alec: Well, that’s the thing that keeps us moving, right? It keeps us championing certain causes, like Black Lives Matter, for example. The only way we can, in fact, move forward is by hoping things can change.

Analogue: Well certain artistic expressions will just describe things as they are and leave them morose or negative. But you’re wanting to make sure your own expressions have a ray of light to them.

Alec: Oh sure, I see what you mean. It’s a hard thing for me to allow the possibility of not getting too down. Honestly, I think we’ve all been tested quite a bit since the pandemic started. A lot of people have resigned themselves to staying bed and that sort of thing. A lot of artists who I know have a lot of doubts going around, and rightfully so, but there are also people trying to reposition themselves and use it as an opportunity of sorts. So it’s always that balance. I just happened to strike upon that when the pandemic started.

Analogue: By the way, where are you today on that spectrum?

Alec: [Laughs] I don’t know. I was just working on a song. I’ve got a lot of sketches and I’m just forcing myself through the end. It’s always dependent on whether or not I find I’m successful in what I’ve done most recently. I would say not yet then. I’m not feeling so good about myself yet, but I have 53 sketches to go through and I’m always excited to listen to them. I’ve made notes for each and scratch lyrics. The process is exciting, but it also leaves me sick to my stomach since I can’t get it right. That’s the norm, I suppose.

Analogue: I think that’s the artistic norm, right?

Alec: Yeah, I think so.

Analogue: Are you pretty kind to yourself?

Alec: [Laughs] Not at all. I’m not kind to anybody else either. It’s a problem. I’m trying to address it, y’know? For example, my first album, I didn’t even want to release it. My mom was the one who said, ‘Just do it. See what happens.’ I’m not kidding. I wasn’t going to release it, but I just decided, ‘Oh, well. This is about 70 percent of what I have in my head, so maybe that’s the best I can do.’ I’ve realized after eight albums that it is the best you can hope for.

Analogue: To focus on the positive there, when was the last time you felt you got something totally right?

Alec: Well, when I listen back to my records, I think, ‘Why was I so down on this at the time?’ There are some where I think, ‘Oh, those are mistakes I wish I hadn’t made.’ However, more often than not, I’m pretty proud to play any of this material. There are a couple clunker lines here and there, but I hold myself up to sometimes too high of a standard.

Analogue: In the editorial process?

Alec: Yeah, lyrically I tend to throw away more than I keep, which is probably common. But yeah, I can be pretty hard.

Analogue: You can be so hard on yourself, but yet you likely also have those moments artists talk about when the muse just comes to you.

Alec: Yeah, that’s true. I remember hearing, and I don’t know if this is just a myth, but there’s that whole Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen conversation. Leonard wrote “Hallelujah” and it took him a year or whatever and Bob wrote “Like A Rolling Stone” and it took him 20 minutes, so the story goes. I understand that as well. I’m pretty sure not every Bob Dylan song worked that way, but I also think that likely—and the is the same way for me—that he’d been working every single day. When you do that, it seems immediate but really there’s a background of work. I also think Leonard Cohen had a tendency to torture himself. [Laughs]

Analogue: Earlier you said that Bazan and Will Johnson and others are good at ignoring the fact that people are watching. How good are you at that?

Alec: I like to imagine that I’ve always been pretty good at that. With the second album where I really made a record that I actually wanted to make, I almost wanted to mess with people a bit with decisions made on the second album. I was immediately tired of being associated with things that I didn’t think had anything to do with my thought process or approach to music. In a way, I wanted to try to tailor it to my own liking.

I’ve always been of the mind that if you’re coming from it from an honest perspective and you can get anybody to pay attention, then that’s the best you can do. So I haven’t really thought too much about who is paying attention to me. I talk to you or someone else and they’ll me what they think and say okay. And I listen to friends of mine. But I don’t go around reading my own reviews or anything like that.

Analogue: Did you ever?

Alec: At the very beginning I did. I was suspicious of the positive ones which is very much my style. After reading them a bit, I realized, ‘Wait, I know what I did on this record. Why am I interested in what they are saying? They’re not telling me anything I don’t already know.’

Analogue: That’s such an interesting tension. On the one hand, it sounds really healthy to not care who is watching or what people think, but you also said the purpose of all of this is about connection.

Alec: You’re right. Mostly when I do these intimate shows with people who’ve been affected by it some way, they’re usually not sitting there with notebooks telling me what I did wrong, you know? [Laughs] If they did, that’s fine, too. But I like to get it directly. I like a conversation about it. I don’t like it just dictated to me.

I think finally what I discovered after all these years of doing it… I never even really liked going to live shows until I started playing them. I started playing them and I wondered why people wanted to hear songs the way we did them on a record. You can just be at home and listen to something better.

It took me years—it really did—to understand what people liked about it was the sense of community that was engendered by going to one of these shows. It’s kind of wild when you think it took me that long, but I’m a difficult character sometimes. I’ll admit it. That’s what I’ve come to discover about the whole thing. The whole thing was to breed this sense of community.

VISIT: Clap Your Hands Say Yeah