It was a few years before anyone cared about Ben Cooper's music. Even then, it was a corporation who called.

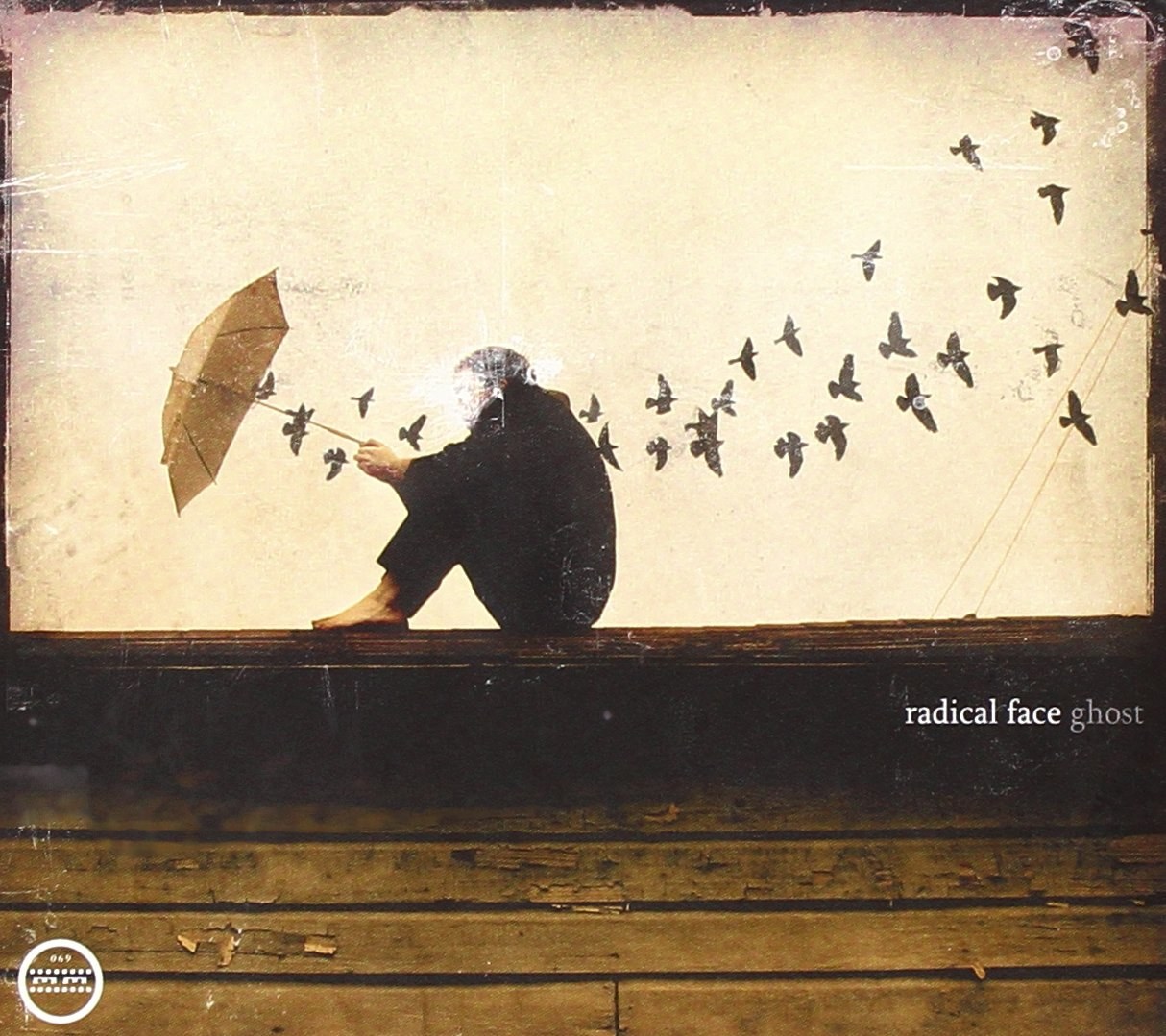

Cooper, the man otherwise known as Radical Face, first released Ghost back in 2007 to the applause of only those closest to him. The label wasn't excited by it. Critics weren't either. Commercially it didn't work—that is, until it did. Three years later, Nikon decided to use the song "Welcome Home, Son" for a commercial and a hit was born.

This last fall, Cooper decided to remaster (or well, master) Ghost for the first time with b-sides and outtakes, a celebration of an unexpected hit that introduced most of us (eventually) to one of the most authentic and gifted songwriters in music today.

Cooper recently sat down with us to recall the old shed in which he recorded Ghost and why touring has always been such a difficult exercise for him.

Analogue: I want to talk about Ghost, which just got a deluxe reissue. Part of what I want to ask about is whether the stories of the birth of that record, how true those are, or whether they’ve been turned into folklore. I’m reading about recording it in a shed, recording it only at all hours of the night, that kind of thing. Sometimes that can be a publicity spin on something...

Ben Cooper: Yeah. I’ll tell you this is where I’m a little bit of an odd one. Instead of it being overinflated, a lot of it’s actually played down.

Analogue: Really?

Ben: Yeah.

Analogue: Can you inflate it to its proper size?

Ben: If I kind of knew how unlikely everything I was doing was, I would never have done it. If I actually knew my odds, I would not even have bothered. Just as far as the way I grew up, I’m one of 10 kids, but I’m the only white guy. I’m from a mixed race family in the South. A huge family. I grew up in a two bedroom house. At one point there were 14 of us there. Definitely below the poverty line. I didn’t come from a family that planned for anything. Just kids keep falling out and there’s no money. In hindsight, it’s like, 'What the fuck was going on?'

I didn’t have my own bedroom. I got my first bedroom when I was 27. That was the first time I slept in a room by myself. So instead of buying a car, I got my first mic. I had a license, but if I got money, I just would buy a microphone or something. There was a toolshed behind the house. It was originally a one-car garage, so not much square footage. Half of it was just the laundry room. The other half I just cobbled together some way to record in there. It wasn’t even a finished toolshed. The floor of it was still dirt. So I just put a bunch of rugs down and built a way to record back there.

I was near a pretty busy road, so I couldn’t start until 11:00 p.m. just because of the buses and stuff. Then the gear I was using, the only reason I used some of the equipment, it’s never been principle, it’s just what I had. I started playing banjo because I found one in the garbage. It wasn’t that I thought banjos were cool. I was just like, well it’s there. I’ll use the banjo. I didn’t play accordion on principle. There was just one in our high school music closet that no one could figure out who it belonged to. So I said, 'Can I have it?' They gave it to me, so I played accordion. There’s no principle or plan. It’s always just been, okay. Here’s the stuff. Make something. It’s kind of funny, because I’ve noticed people will almost apply that aesthetic thing to me, almost like it’s a “acoustic instruments are more pure” or something. It’s just what I had. I’m not that principled about it.

Ghost was made under pretty terrible conditions. One of my family members had died right when I started writing it. It was my sister. She was two years older. It was really just kind of a record about grief. I didn’t know how to talk about it, so I wrote ghost stories. The framework I got for the whole record came from a visit to a friend in Gainesville. Just happenstance that they were renovating the house next door. It had a plaque on the front. A circus troupe used to live there in like the early 1900s. There was this guy, the guy working on it was great. He’s like a caricature of a movie. He’d be the narrator of the story. He was like, 'Hey man, you want to come check this thing out?' He let me just go around the house with a flashlight.

There was no electricity, and this house literally had trap doors in it. Secret passageways to staircases that were hidden. It was super weird. And then I went up in the attic, and I found old letters in boxes that no one had done anything with. It was just literally the weirdest, creepiest house. And I had a blast. I was in there for like two hours, reading. It was this whole history that I stumbled on in the attic. Because I was sitting on a stoop next door. That’s it.

I was kind of already dealing with a lot of mortality questions, anyway. But then you have this other one of these people who are dead, and they had all these stories laying around. And I kind of like the idea that we haunt everywhere that we live. If you live in some crappy apartment complex, but you probably left behind little weird things that you just didn’t think about. You changed the color and course of that space. I thought that was kind of a fun idea, that we’re all just haunting everything all the time. It was a culmination of all that stuff. But there’s no reason any of this should have worked for me at all. In hindsight, I have no idea what happened.

"There’s no reason any of this should have worked for me at all. In hindsight, I have no idea what happened."

Analogue: How shocked were you when Ghost began to take on the life it was going to take on?

Ben: That record flopped. It didn’t do well. I really didn’t get along with the label I was on, Morr Music. We really butted heads about the cover. They just hated the artwork I was doing. They did not like the album itself. They were like, 'It’s just too slow. Mixes are murky. I was really conceptual and was like, 'No it shouldn’t be that loud. It’s supposed to be almost like hearing a voice from a room over or something.' They were like, 'Yeah, that’s cool, but people want to hear the voice.' So we, from the get-go, didn’t get along about it, to where I almost threatened to walk. I was like, 'Just don’t put it out. You can just kick me off. I’ll just put it on my website. Eventually, they begrudgingly released it. Didn’t get any good reviews. Nobody liked it. On to the next one.

The other band I was in at the time, Electric President, was doing a lot better. I just kind of figured, 'Well, no one wants these.' Granted, it felt like a weird record. I was like, 'I get why it’s maybe not going to be very popular.' So that was that. No one talked about it. It was done. It was like 3 or 4 years later, Nikon in Europe reached out about using "Welcome Home." At the time, I was stoked for any kind of income. I was like, 'Yeah! Whatever.' I was like, 'For real? You’ll pay me?' Then, 'Yes, do whatever you want.'

It’s kind of funny where people talk about selling out. At the time, I think it was maybe a little more of an issue. Now no one cares. They’re like, 'Good for you. You earned something.' There’s no stigma. But even at the time, I was just like, 'Yeah, whatever.' I’m still more or less living on a couch with 13 other people. I’ll take whatever.

Analogue: I can’t believe it was 3-4 years later!

Ben: Yeah. No one cared. No one liked it. I really thought that was just a whoops. I never planned on playing it live. This was just me by myself, personal work. I didn’t think I had an audience, because the other stuff I was doing was more electronic and more of what was going on at the time, at least a little. So yeah. The record came out in 2007. I finished it in 2006. And then, I think I got that call in like 2010. That’s really unlikely. Normally after 6 months, they’re like, well, that record did what it’ll do. Go make another one.

Analogue: Does that mean this remastered edition feels like a proper release? Like, 'This time around, let’s give it its due.'

Ben: Yeah, because even the first time around, this is actually the first master. The record was mastered, and I didn’t know what mastering quite did at the time. I went to New York. I had a friend who lived there. I got a plane ticket and the label paid for the mastering session. I remember she had just moved into this apartment, and it was in the middle of the summer, and she didn't even own a ceiling fan. That’s where I found out New York in the summer is miserable. No one tells you this. This is horrible. I’m from Florida. This is worse.

"I didn’t say anything to the label. I just went home and re-mixed it and gave them that. It was never actually mastered."

But I went to the mastering session, and it was fascinating, but I didn’t know what he was doing. So me being there, I quickly figured out that I thought mastering would solve problems that I had in mixes, and I found out that mix problems are solved in mixes. You have to fix it before it gets there. So I sat in on the mastering session, and I was like, 'Oh, this actually highlights things I thought it would fix.' I didn’t say anything to the label. I just went home and re-mixed it and gave them that. It was never actually mastered.

So it was an expensive lesson, because I owed that money back to the label. They paid for it. So I’m like $2 grand in the hole for a mistake, and I was like, 'Oh shit.' So I’ve never made that mistake again, but that’s how I learned it was in the room, which was really embarrassing.

This time it actually got mastered. It was the first time it was really mastered. When I got the rights back, part of the fun was, we talked about putting it back out. My manager said, 'Do you have any b-sides from that time?' I was like, 'I do, but they were b-sides for a reason. I never put them out because they suck. I don’t want to add them.' I know sometimes that forensic thing is kind of maybe interesting, but I always felt bad for like Kurt Cobain, when they go, 'Hey, we found some demo he never intended you to hear.' That’s taught me that I need to burn all evidence of all my bad songs, because if I die horrifically, and someone wants to find those, no. Those are getting deleted from every hard drive. Any physical copies are gone. Just don’t do that. You kill your babies for a reason. There’s a reason I didn’t finish it, because I knew it wasn’t good. That’s the whole fun thing about art. You get to make a million mistakes and just put out the 10 that work. People go, “Oh, you’re really talented.” You’re like, sure, I have a graveyard of babies behind me, but yes. Here’s the 10 that worked.

But yeah, instead of me digging into b-sides that I thought were embarrassing, I kind of have a rule that every tour I change the songs. Because if I play it the same way over and over, I get really bored. So every time a new person comes in or something, we’ll just do a new arrangement. We’ll change keys. We’ll really mess with it. Some songs, over 10 years, changed so much, I was like, 'I think it would be more interesting to show what has happened. What happens to material as it mutates?' Sometimes you get a request from a TV and film thing, where they like the song, but they don’t want vocals. 'Can you do something a little more soundtracky with it or something?' Most of those don’t land. You do the work and they don’t run it.

But I have all this other stuff. It’s not b-sides, but it’s post-record. I thought it would be more cool to document that, because it’s more interesting to me. So it ended up being 12 new recordings that have happened over the years or like I got the people I hire for the live band, mostly just friends I’ve known forever, but I just got them all to come in and play it. So yeah, it was kind of a different way of approaching it. But I figured if I got the rights back anyway, I can do whatever I want.

Analogue: You’re on the road for the next few months. Is that a good place for you? Do you enjoy knowing that’s coming up, or is it like, let’s hold our breath and dive in?

Ben: This is something I’m working hard on. My general view of touring is pretty negative. Not for the shows. I actually like shows. I think playing music with people who want to hear the songs is really nice. Shows where you have to convince people who are not interested in what you’re doing are a lot harder. I would rather have loud music if I was going to do that. There’s nothing worse than when you’re the dude with the acoustic guitar, and no one is interested. You have no way to push back. You’re like, 'Aw man, this sucks. I’m at a fight with mittens.' These are shows where typically I only do them now if people ask. It’s not material that I’m excited to revisit all the time, just psychologically speaking.

Tours are exhausting, but I’m actually trying to change the way I feel about that. I’m working on it. I have a good therapist. I’ve never done a tour where I could also ask a therapist for advice. So that’s really cool. I’ve just been working on trying to remember what shows are for, because I didn’t grow up going to them. For me, music is super headphones. I’m most connected to music listening to records on a bus or going on walks. That’s what I think about when I think of music. I’ve been to shows and had a good time, but that was an anomaly. That was not something I did often. It’s not how I learned about music, so I actually have spent the past month being kind of a weirdo and interviewing everyone. 'What do you like about shows? What do you remember? What feeling do you take away? I don’t have enough perspective on my own, to be like, 'What is it about a show that’s really memorable?'

I realize how much more communal they are. And I’ve had that experience, even when I thought about it, I was like, 'I’ve been to a show, and it’s been the closest I’ve ever gotten to church.' Where everyone in the room is feeling the same thing, and you can tell somehow. So I’ve been really trying to rethink how I think of it, what the purpose is. I think when you expend energy with some sense of purpose, it can be fulfilling instead of just tiring.

Previously, I think touring was mostly just tiring, because I also am physically completely not built for it. I have a back injury, because I thought I was going to be a professional skateboarder when I was a teenager. My back goes out all the time. I recently found out from a vocal doctor where they put a camera down your nose and they show you what’s going on inside you. It’s some crazy shit. I found out that paralysis in one of my vocal folds. It only moves about 15%. So I’m very quiet as a speaker, in general, and my singing voice is really quiet. So I could lose my voice on tour really easily, but I could never understand why it would come back in a day or two. Because normally if you lose your voice, it’s kind of gone for four or five days. Mine would return really fast.

I was like, 'What is going on?' So I finally found out and she said, 'You’re not losing your voice. You, to produce volume, my neck muscles are making my vocal folds connect. So that’s why when I sing loud, I have worse pitch control. And she said, 'You’re not losing your voice. Your neck is getting too tired. Until you basically stop talking and they can recover, which only takes about a day or two, you’re just out.' So now that I know how it works, I think I can do this all a lot better and a lot smarter. At the time, it just felt like I could lose my voice at any minute, which just makes you paranoid. Being on the road, you’re like, 'I don’t even know if I can sing tomorrow.'

So now I have a plan, and my perspective is different. Touring actually sounds pretty interesting, and not just weeks of low-key anxiety, and I don’t know why I’m doing it. That’s kind of what it has been.

Analogue: That sounds like a great turn, because the other sounds miserable.

Ben: It is kind of miserable. And I’ve never made money on tour, because I have to hire a whole band. The advantage is if someone uses your song on a Nikon commercial or a TV show or something, it’s just you. So you can make a good living that way. But it’s gambling. Touring is something you can do consistently, but when you have to hire five people, or in my case, four, I pretty much start at negative a lot and I tour my way back to zero and then go home. It’s not like it was even financially anything.

So with no purpose, and I’m earning nothing, yeah, it was just miserable. I was like, 'I need to rethink this or it will always be miserable.' So now it went down to a four-piece, so I will be an equally earning member. I’ve been interviewing people for a month and realizing how nice shows can be, and it’s even helping me think of the kind of show I want to play. So yeah, suddenly I’m really curious. And once I’m curious, I will probably enjoy it.

VISIT: Radical Face