I am fully aware of the reasons I should probably not love Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe.

I know the clarion trumpets are fake. They did not come from tersed lips forcing air through a mouthpiece, but from the fingers of Rick Wakeman on plastic keys. But back in 1989, they stirred my spirit.

I know the lyrics are pretty trippy at times. But back then I wondered if maybe we actually were the first to “learn the universal consciousness divine.”

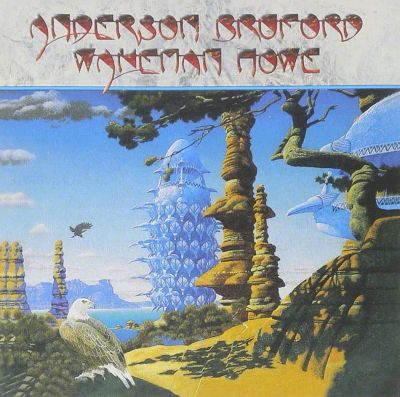

I know the Roger Dean cover, what with its eagles and snakeskins, looks a little ridiculous now. But it was so cool in the late 80s.

I know Jon Anderson’s falsetto is weird. But I can sing along, and I did (and I do).

Teetering at the edge of sincere and synthetic, the one-off eponymous album from Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe is a defining Ebenezer in my music journey.

Okay, let’s get this out of the way. The name is bad. The annals of music hold a rich history of bad band names. Limp Bizkit, Hootie & the Blowfish, Hoobastank, and The The (I put that one last just so I could string three articles together) seem almost intentionally bad. They’re certainly memorable, meant to stand out and provoke discussion, I suppose, regardless of the quality of their music.

Then there are the law firm bands, perhaps not intentionally bad but certainly lazy. Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. Emerson, Lake & Palmer. (Both are lamentable for their lack of an Oxford comma.)

But Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe was not just a law firm band name, it was so named because of law firms, and lawsuits among the various members of the band Yes. My YesYears box set has a massive family tree for the band in the liner book, and I can think of no band more deserving. Acclaimed musicians have joined, left, and joined again through the decades, spinning links to bands like King Crimson, Asia, and GTR, bands that filled my BMG free CD orders in the 80s. By 1989, founding members Jon Anderson and Chris Squire had parted ways, with Squire taking the name “Yes” with him. So, it seems, the Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe moniker rose not from laziness, but from spite.

To be clear, there are no commas. No ampersand. Just a pragmatic, octosyllabic, non-alphabetical name that is neither inspiring nor memorable. Unless you know your 70s prog rock. Then, these names are instantly recognizable as four fifths of the 1971 iteration of Yes. And if your name is that bad, why not make your album eponymous? Rock gives courage.

1989 was a glorious year for musical diversity, so if you wanted to make a synthesized prog pop rock album, that was the year to do it.

We called it ABWH back in 1989, when we played it loud in a darkened room through those blessed speakers on old stereos that stood as tall as a child, before the days of tiny surround sound speakerettes. You need big speakers for the opening song, “Themes.” It’s sparkling. Twinkling piano dances with portamento piccolo (synthetic, of course) for a full minute before, at exactly 1:02, Bill Bruford’s drums (also synthetic) kick the reverie across the room. Sometimes I’d turn the volume up loud to hear all the dancing notes, and forget the drum blast. I’ve jumped out of my chair more than once during that song.

What follows is, in retrospect, a fascinating amalgam of music. There are vestiges of prog, in song structure and in lyrics that long to be epic. There is 80s rock, with Steve Howe’s guitar voicing the clean mids and highs of the decade (and maybe borrowing a bit of the Trevor Rabin vibe from 90125). There is synth pop, in “Long Lost Brother of Mine” and the bizarre “Teakbois.” The year-end Billboard Hot 100 chart for 1989 boasted Chicago, Bobby Brown, Poison, and Paula Abdul in the top four. It was a glorious year for musical diversity, so if you wanted to make a synthesized prog pop rock album, that was the year to do it.

I still pull the CD off the shelf often, and I still hear the heart beating underneath the sheen. I love the defiance of “Second Attention.” “Birthright” is a politically aware powerhouse with the most honest lyrics on the album. “We are them and they are we” resonates loudly today.

It is five songs in when the album really gets me, still today. Wakeman’s piano opening on “The Meeting” is so lovely and delicate, and Anderson’s voice is – maybe for once – exactly right. My gigantic 80s stereo had an off timer on it, and Anderson sang me to sleep in that song many a night.

Then it’s Howe’s turn, opening “Quartet” with the same delicacy. I put this song on a mixtape for my girlfriend, because the sentiment is so caring: “I wanna learn more about you… I’ll give you my heart, my life for life.” If you don’t know this album, listen to “Meeting” and “Quartet” and revel in this pair of love songs. They namedrop Yes songs, they tease spiritual metaphors, and they reveal four virtuoso musicians through the quiet, not the noise. Oh, and by the way, that girlfriend is now my wife of 25 years. That’s a powerful song.

ABWH is not exactly obscure. It was certified gold, and even received a 25th anniversary reissue. But you definitely need to know to look for it, and you definitely should. Play it in a darkened room, with big speakers. Just turn them down about a minute in.