I’m an elevator kid pushing buttons when I wanna go home

But my g-g-generation hadn’t even got a name of its own

We just buy what the TV sells

And almost never stop wishing we were somebody else

But tonight in the dark I can be myself

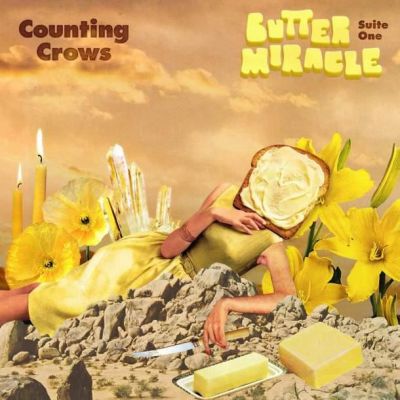

If August and Everything After ever gets the jukebox musical treatment (a la Alanis), the introduction to “Bobby and the Rat-Kings,” which is technically the fourth song included in the cycle hereby known as Butter Miracle Suite One and doesn’t start until roughly the 13:30 mark, is going to be our entry point.

Wild and tattered like Steinman-cum-Springsteen, featuring Adam Duritz singing as vocally free as maybe he hasn’t been since as early as “Angels of the Silences,” the scene is set quickly and with elegant finesse. Words build on words to paint the story of a young rocker in today’s post-COVID world trying to find an identity in a world which seems almost predestined to deny one. It’s a world where false nostalgia reigns, and if only they could live through Bobby and the Rat-Kings for a few more songs, then maybe there’d be a sense of hope.

Because when Bobby and the Rat-Kings go away, we’ll never be the same.

When I read the press copy surrounding the Crows’ first new songs in seven years, I wondered what Adam Duritz’ writing would sound like when he’d seemingly found happiness. Butter Miracle, it turns out, is a nostalgic journey told backwards.

“The Tall Grass” blends memories from throughout the character’s life, a rabbit he killed during a hunt dredging up harsh memories of love and loss, childhood abuse and tragedy. “There are trains that can take a girl to Paris,” Duritz sings. “There are planes that can bring you home / and there are some of us get broken when we’re children / and we never get it back once that is gone / and I don’t know why.”

“Elevator Boots” is the flashback to Bobby’s development as a musician, told in a blend of third person at first, then through Bobby’s POV as the memory comes to life of the woman named Alice who served as his artistic muse.

She gets her chance to shine on “Angel of 14th Street,” where we sense that music was a savior from a life of drowning in painful memories. Duritz summed it up nicely in a recent Rolling Stone interview: “Everything we did makes us who we are, but that doesn’t mean we have to drag it around like it’s a ball and chain.” The mid-point of “Angel,” at which we’re ten minutes into the free-flowing suite, hits hard with its hints of what must have been Duritz’ real struggle as he dealt with a lifetime of mental illness, both himself and through his many characters:

Yesterday when we get older

We’ll look back at all the times

We had to put a new face on

Instead of just walking away

To paint your face black and blue again

Wake up! Wake up! Wake up!

Wake up new and put on clothes

And make you feel like you’re not broken

But all the build-up succeeds in blending the nostalgia and the often hidden trauma of life. Nostalgia is a ghost of memory, he implies, a recording of our life that we can’t take as more than an unreliable narrator. So if we can’t trust memories, he asks, why let them strangle us and keep us from making new ones?

That’s what makes “Bobby and the Rat-King” so fucking infectious! In this jukebox musical, we’re trying to make our own way through false-front memories of a nostalgic world that, if you tilt the lens slightly, turns out to be a ghost itself. Tying the message to the avatars of a group of young people in today’s generation taking what they can to build their own truth, “You can almost lose your heart / hoping for something better ‘til it tears you apart,” Duritz sings and it’s so real it hurts.

I wondered what would happen when Duritz found a balance between his darkness and his light, and it turns out that balance brings about the best songwriting we’ve seen from Counting Crows since Recovering the Satellites. This is essential, exciting, truthful listening, and it’s worth far more than the seven-year wait and 19 minutes of uninterrupted exposure to experience.

VISIT: Counting Crows