“That’s weird. I didn’t know that R.E.M. broke up. I mean, I haven’t really paid attention to anything after Monster.”

That's a direct quote from a workmate. He's an intelligent friend I respect and enjoy working with. I never would have guessed, after multiple conversations with him about R.E.M., that he was unaware that they were no longer together.

I wondered: Is that how most of us feel? Did we unfairly write R.E.M. off two decades before they were officially finished?

I don’t know. I’ve spoken to plenty of people who have a soft spot for New Adventures In Hi-Fi and Up, two albums that seem to define what it means for a band to be “ahead of their time." I, myself, have a soft spot for Reveal and believe that, when I finally get around to listening to it, Around the Sun won't be the atrocity many claim it to be.

Furthermore, Accelerate and Live at the Olympia in Dublin, not only sold well, they demonstrated that the band was still very much at the top of their game—a functioning, well-oiled machine that expertly dodged the political minefield that nearly wrecked U2 and the far-too-weird indie sentiment of Radiohead.

R.E.M. was just a great band with great songs and years worth of experience under their belts. But that alone doesn't sell records.

In case it wasn't obvious, I've come to praise Collapse Into Now, not bury it. Of all the R.E.M. records I could have picked to write about, this one is perhaps the most difficult to quantify. It’s arguably the most forgotten 'final album' of any band I've followed for multiple decades, and it's also like capturing an identity crisis in full bloom.

Like many '90s and 2000-era Neil Young records, Collapse Into Now got one or two listens and then got pushed on the slush pile of mp3s, buried somewhere between Lykke Li and the last TV On the Radio record I never listened to, either. I had made up my mind that I was going to love Collapse Into Now, I just didn't need to love it immediately. But like a patient lover, the album sat silently, watching as I courted temporary flings, biding the time until I wizened up.

It took almost seven years but I returned to Collapse Into Now by picking up a used CD copy for a whopping $3 at my local record store. (I still buy CDs, yes. There's no reason not to.) There it sat sandwiched between dozens of copies of Monster, a lone copy of Fables of the Reconstruction, and all of the unopened copies of Around the Sun in the greater Southeast.

I'll try not to dip into hyperbole, but hearing the opening track, "Discoverer," spill out of the speakers and then bleed over into "All the Best," caused a catch in my throat; goosebumps that rattled up and down my arms. "All the Best" is one of the finest tracks in R.E.M.'s post New Adventures In Hi-Fi catalog. Hell, the first three tracks on Collapse are up there as possibly the best three opening tracks on any of their records.

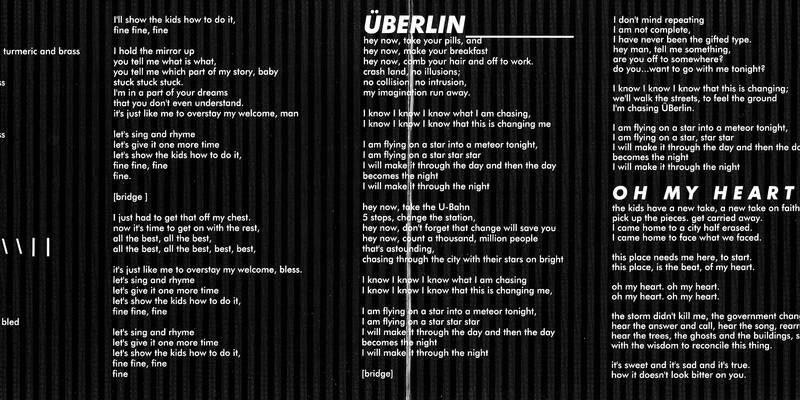

"Discoverer," despite its first-glance throwaway feel, sticks around to offer up "All the Best," a song that brazenly tells the "kids" that R.E.M. are going to "show" them "how to do it fine." And when Stipe sings "I'm in a part of your dreams / that don't even understand," I don't have to wonder if he's right. He's my crush with eyeliner. He's the Cassandra of contemporary songwriters; the oracle that everyone hears but doesn't listen to.

Optimism is no small currency in this, our era of division, our era without an R.E.M. to call our own.

If the first two songs on the record are R.E.M. climbing up the mountain and planting their flag, then "Uberlin" is their slow, intentional decline into the realm of terra firma. It's a song where the narrator is quite literally putting her feet on solid ground—walking, chasing, and traveling, through streets at night. Behind her is something that she knows "is changing me." But her routines—"take your pills," "make your breakfast," "mak[ing] it through the day"—are interrupted by bright nights and lonely thoughts and constant, unceasing movement.

Who hasn't been there?

"Oh My Heart," "It Happened Today," and "Every Day Is Yours to Win" are passable songs within the band's oeuvre—"passable" meaning that they're still top-tier but fall a bit short in the context of the album and its preceding elements. If nothing else, "Oh My Heart" is one of the few sincere love songs Stipe helped write (the album credits indicate it was written by all band members + de facto fourth member Scott McCaughey), and "It Happened Today" has some sneaky backup vocals from Eddie Vedder that most people never uncovered.

For Side B, the "Y-Axis" as the band named it, the album bursts forth with allusions to a dark future, slivers of hope, and guest appearances from Peaches and (who else?) Patti Smith. Aside from its quizzical title, "Mine Smell Like Honey," is relentlessly catchy, a less cloying version of "Shiny Happy People," and "Alligator_Aviator_Autopilot_Antimatter" wins for its title alone but also because it stands as, chronologically, the final four-on-the-floor rock song that R.E.M. delivered to their fans.

"Me Marlon Brando, Marlon Brando and I" cuts a piece of the cloth from "Uberlin" by dousing Mike Mills' piano keys around slippery vocal lines to produce something akin to audible starlight. In "Marlon Brando," I hear pieces of "At My Most Beautiful." The key has changed from major to minor but I don't think it's a mistake to correlate the two songs. The final tracks on Collapse, the aforementioned "Marlon Brando" and "Blue," harken back to years of R.E.M. past. "Marlon Brando" recalls the sunken but lighthearted feeling of Up, their first album post-Bill Berry, and "Blue" is almost certainly a follow-up, if not an outright sequel to "E-Bow the Letter" from New Adventures In Hi-Fi.

Much of "Blue" takes the same tonal structure as "E-Bow the Letter." The major difference being Stipe completely abandons any sense of "singing" (he at least tried to sing/speak on "E-Bow") and just reciting a litany of sub/conscious thoughts. I haven't looked at the lyrics to what he's saying; like Stipe has always maintained, the lyrics are just as much a part of the song as the bass or guitar, they're perfunctory in all senses, often not particularly special or attention-worthy. But it's hard to deny that Stipe became one of the best lyricists of the 20th century. And his words only grew in stature with each release. Whatever it is he's lamenting or rejoicing about in "Blue," he lets his cohort, Patti Smith, carry the atonal melody line. But he gets to bring everything down solemnly with a final phrase: "20th century / collapse into now."

If that were the end, it would be a stark note to end on, and also in direct contrast to the final lyric on New Adventures In Hi-Fi: "20th century go to sleep / I'm not scared / I'm outta here." But the lines loop in on each other. The band knew this would be their last recorded song on their last album, so it certainly seems intentional.

But "Blue" isn't the full stop. Lo and behold, the opening guitar riff of "Discoverer" returns, sans lyrics. "Discoverer" lifts us back up and it's enough to make me wish they had never said goodbye. I am glad, however, they left us with only a hint of optimism.

Optimism is no small currency in this, our era of division, our era without an R.E.M. to call our own. "Aluminum tastes like fear / adrenaline pulls us near," Stipe once intoned, humming us all into an awakening rather than submission. Optimism was in bloom when he sang that in 1997. Maybe one day it will be again, but it will have to be without R.E.M.