[Ed. Note: The following essay discusses suicide and drug use and may be sensitive to some readers. Please be advised.]

I saw Frightened Rabbit nine years ago.

April 2010 and I met a friend at the newly opened Unitarian Church Venue in downtown Philadelphia. The lack of air conditioning in the church basement was quickly obvious. The broad but squat, cellar-like concert space began to glow with the heat of many bodies and the warmth and humidity of the quickly-filling room was a shock to the system.

A friend brought four women along to the show; one, a girl he was dating, two other tagalongs, and one girl who was EXCITED, in a way that my buddy (who had heard the band but wasn’t quite yet a true Frightened Rabbit listener) had no understanding of. She was a true fan, thank all gods.

Recognizing the excitement we held pent in our youthful vessels, we immediately set upon one another.

“You like Frightened Rabbit?”

“Yeah, of course. This is amazing. Can you believe how hot it is?”

We two had face-splitting grins in anticipation of what was coming and also at our companions who had no idea of the music that they would experience.

The show was prompt as we weren’t allowed much further introduction but the music’s beginning drew us together as we had a connection, however tenuous, however deep. We were thrust towards each other as the songs and the music willed it and we were soon touching one another, fingers entwined and hands grasping. We were dancing, jumping around, she and I, like people with years of physical comfort invested in the other, pressing to each other how young lovers do in the deepest of nights. We carried on carrying each other through the whole concert, clutching and clinging, like newlyweds washed overboard on their honeymoon cruise; alone with only each other and buffeted by deep swelling waves of sadness, desperation, beauty, joy and hope. All because Scott Hutchison’s music yearned in every line for closeness and connection.

This should be the part of the story where I say, “Soon after the concert we began to date and now we are married.” But we didn’t and we’re not.

This should be the part of the story where I say, “Soon after the concert we began to date and now we are married.” But we didn’t and we’re not.

Once the lights were up we parted with little fanfare, slightly confused and maybe embarrassed. I can’t even remember how she looked that night or her name. Is that a sad ending? I don’t know. We’ll always have Frightened Rabbit. Sadness and Death are strange.

I cried once when my grandmother died. She was a great woman: a teacher, a traveler, person of love and stern gentleness. Why did I cry? I don’t think it was for her. She lived a Life and a long, good one, at that. It was for my loss, right? Funerals are for the mourners not the deceased, they say. I think I cried from shock and confusion at the bald-faced reality of death: someone taken away from me without my approval.

Sadly, I won’t claim to be anywhere near completely in touch with my emotions or why I feel them, so part of me was puzzled when I cried multiple times for multiple days after the news of Scott Hutchison’s suicide. I had to avoid the subject when talking to people who were strangers to Frightened Rabbit and Scott’s music, because the grief would rush up in me and spill out the corners of my eyes in polite, dry-eyed company. I hugged friends that were fans and batted eyelids against building waters. I watched YouTube videos in private like a masochistic goth girl and ugly-cried through solo sets and full band performances alike, but it was the solo videos that hit hardest. If you are or were a fan I recommend you never watch the video below. (Obviously, NSFW if you don’t want to cry awkwardly around your coworkers.)

The too-pat symbolism of Scott performing all alone on a tiny boat, singled out and removed from the people around him, his affable, jokey charm in the beginning and the admission to a child in the audience of sadness and heartbreak, leading to an equally frank performance has a brutal effect. I don’t know how many times I’ve thought angrily, tears drying, “Why’d they have to put him in that damn tiny boat?”

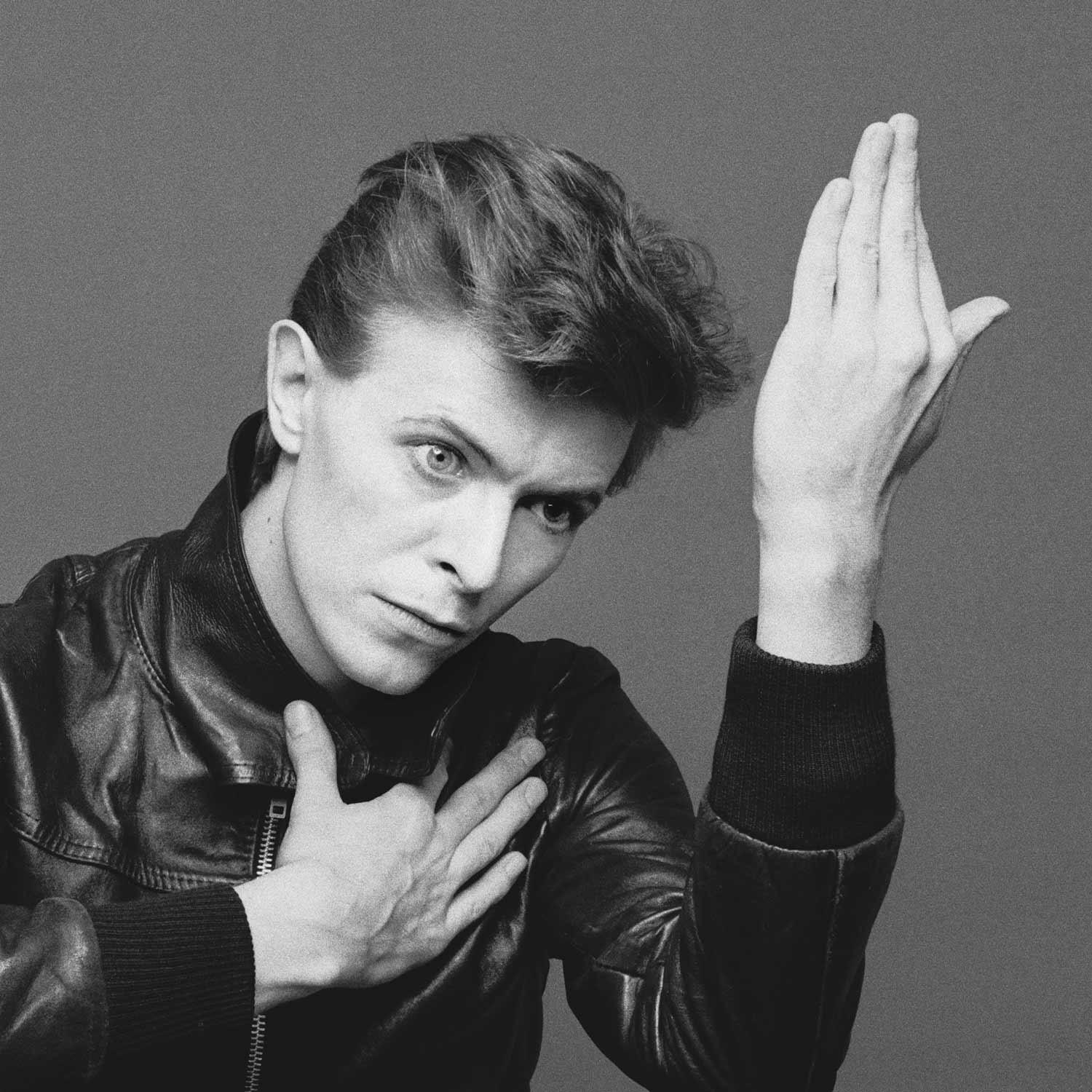

There is also a voice in me like an internet troll saying “Boo hoo, aging hipster. Why don’t you go back to crying about David Bowie, another person you never knew?”

I always hate to admit when a troll is right but I did cry once about Bowie’s death. I was upset when I first heard the news, yet it took two days for me to actually admit tears. But why did I shed a tear at all? I never met Bowie, never conversed with him, never had Turkish coffee with him. (Though if I had, through some strange miracle, gotten the chance to hang out with Bowie I’m sure something as equally random as Turkish coffee would have transpired. Perhaps a ride on matching unicycles, as well.)

Bowie was nothing if not a carnival. But was he a carnival, or was that just another persona he presented?

Truly, I did not know Bowie. Bowie was unknowable (even more so than most cultural figures) and that was part of his power. He wasn’t a person to his fans (to me) as much as walking, talking, singing validation of weirdness and change in human form. A validation that it is okay to be you, or the you that you want to be that day, or even someone else entirely, and also that changing and growing does not invalidate the person you used to be, nor that growing away from your previous self means that you are now fake. No matter the decade or the character he was portraying or singing through, Bowie just was, warts and all. I hope his example gives others the comfort in their skin that he gave to me. Bowie was myriad and mysterious and ultimately the most human example we could hope for from an otherworldly person.

Also, his music did not suck.

I think when I cried about Bowie I was feeling something of the loss you feel when you find out about Santa Claus. Something mythical, magical and previously eternal is ended and is snatched from you and the world you inhabit, and though I was surprisingly sad when I heard about Bowie, I only cried once because this loss was only another change, and if he showed us one thing it was fearlessness in the face of change.

But Bowie was the only one of the three men that did not die from suicide.

When Anthony Bourdain took his own life in a hotel room in France, the celebrity chef was mourned by many around me on social media and also in my day-to-day. So why is it that, despite the fact that I have read two of his books, seen almost the entire run of both his travel shows and been impressed by his strange, renegade code of integrity, that I did not cry to hear the news?

He was older, but not old really, and nobody can deny that he lived a capital-L Life. And maybe that has something to do with it: not his life so much, but the way he lived it.

The more I think about it, the more I’m sure it wasn’t the life he managed for himself as much as the style in which he accomplished it. Sure Bourdain saw all the things, ate all the things, and did all the things many would give anything to do and experience, but the part that affects me the most is that he did it all his way, with very little compromise.

Bourdain was a man who had compromised many times before the airing of his first travel show. He had compromised his integrity in restaurants, his body in his drug use, and possibly his private life for his work. By the time most of us were watching Bourdain reveal the great cultures of the world through cuisine, he had stopped compromising in most of these areas. Eventually, though, he used all his charisma and all the notoriety gained by writing Kitchen Confidential to segue onto television and gradually refined the type of show he wanted to be a part of, leaving “No Reservations” and the Travel Channel behind for Parts Unknown and CNN. The new show surely should have been called "No Compromises" as he’d left Travel Channel because of frustrations with new ownership and practices he found to be of a slippery moral character.

Bowie was unknowable and that was part of his power. He wasn’t a person to his fans as much as walking, talking, singing validation of weirdness and change in human form. A validation that it is okay to be you, or the you that you want to be that day, or even someone else entirely, and also that changing and growing does not invalidate the person you used to be, nor that growing away from your previous self means that you are now fake.

The new show on CNN was deeper, darker, more expansive, and more focused, more complex, more political and more philosophical: something a person of lesser esteem could have never gotten produced.

I did not cry when I heard about Bourdain. Many of my personal friends who were big Bourdain fans are also men and there isn’t a lot of crying around other men in most circles, so I cannot truly know their full reactions but there was a lot of gnashing of teeth and the subject was always in the corner of any casual conversation ready to be unleashed like a caged, hurt animal, for several days after.

No, I did not cry about Bourdain. Until tonight, months later watching the final episodes of “Parts Unknown.” The tears came quick and left just as quickly. But I know what few, mute, male tears I shed were more for my own loss than for Bourdain. I will never watch another Parts Unknown with Anthony’s deeply beautiful, broadly misanthropic, yet acutely sincere love of humanity on full display.

I can’t presume to understand Bourdain’s reasoning behind his suicide. Any such attempt by anyone is folly. If you need to make a reason up for your own comfort, please do so, but keep it for yourself. A few had hypothesized that he had returned to drugs and that never felt right to me. (The toxicology screen came back negative.) I think my lack of initial sorrow is once again not because of the what or the why, but the how. Because he died as he lived in his later years, by his own rules. It was his choice, in his manner, in the place that he chose.

Several of my friends have expressed anger at his selfishness, citing his daughter who will grow up without him, and the basic selfishness of suicide in general. They have a truly powerful argument that I can’t and won’t attempt to dispute. I don’t pretend to say that suicide is a noble thing in any way and I encourage anyone with thoughts leaning towards that end to talk to someone, but I feel it is also tough to just dismiss an individual’s strong desires regarding their own life. I won’t refute the selfishness of suicide as a general choice but there is also an aspect of selfishness in asking a person to withstand a life they can no longer endure—or wish to endure—because you want them to. It’s not so easy to merely say Bourdain was selfish in his actions because we didn’t know him. Perhaps no one did. It’s not for me to say or worry on. For me, personally, suicide holds little glamour and none of the gracefulness that I would hope for in my own death.

What’s the blues when you’ve got the greys?

Like Bourdain, I never knew Scott Hutchison. But I understand that Scott had written his own death for himself years ago, like a writer obsessed with foreshadowing. Why, though, does his self-written ending sting with a lack of grace and beauty despite the slow development of theme and context? It is not like other celebrity deaths we have known: lightning strikes of unexpectedness. Scott’s death is clearly spelled out in much of his art and it is not all that hard to read most of his music as a longform suicide note.

I was fortunate to get a start on the ground floor with Hutchison’s group, Frightened Rabbit. A dear friend with an ear to the musical pipeline made me a mix CD back in the brief window when folks did such things. (Golly gee shucks, those were simple times.) This was a cd-dvd, though and had many albums on it, mostly newer artists I was unfamiliar with, which was great. Sing the Greys, Frightened Rabbits’ first album, was on it and though this disc held several fun albums on it, Scott and company’s debut release was a stand out.

With some hindsight, however, I see that the depression was there from song number one.

The album kicks off with “The Greys,” an opening that asks, “What’s the blues when you’ve got the Greys?” Hutchinson clearly draws a line in the sand between feeling sadness and true depression, which has little to do with “the blues.” Though, for a song about feeling like the world is empty of color as its main metaphorical conceit, “The Greys” is surprisingly upbeat in tempo softening the blow of the deeply depressive lyrics—until you read them without the music. Another reading of the words could be a person dealing with substance withdrawals. Once again, I won’t pretend to know the truth of these lyrics in regards to Scott’s life, because, like Bourdain, I have no true understanding of the reality. I could speak towards the specific relevance of these words in how they connect with my own life, but prefer to see them as an all-encompassing referent towards those dealing with some sort of chemical imbalance that has them removed from the world of emotion and left them frozen and in a stalemate.

The new show on CNN was deeper, darker, more expansive, and more focused, more complex, more political and more philosophical: something a person of lesser esteem could have never gotten produced.

My first-blush love of the inaugural FR album aside, it is hard to ignore the power of their second release. In fact, The Midnight Organ Fight is difficult to refute as the FR album. Despite all inclinations otherwise and all personal wriggling towards other possible options, this is the quintessential release.

On a normal album, putting a song as epic and emotional as “The Modern Leper” as the opening song should be a disaster: the filmic equivalent of putting the climax of the movie at the beginning, leaving the rest of the picture to be one slow let down for the viewer. Only Frightened Rabbit could pull it off, though a listener won’t be blamed for, upon first listen, going back to hear “The Modern Leper” again. Ultimately the rest of the album is strong enough to not capsize under the weight of its foremost song. If no other song on the rest of The Midnight Organ Fight reaches the purest form of “sing at the top of your lungs” powerful, they most all reach you in other ways. What would I be without the folksy sincerity of “Old, Old Fashioned,” the glowing energy of “The Twist,” the darkly luminous “Head Rolls Off,” the droning emotion of “Backwards Walk,” the sacred profanity of “Keep Yourself Warm,” the dry simplicity of “Poke.” What would I be without these songs? A lesser goddamn person is what.

The too-pat foreshadowing truly begins in the next to last song on this album: “Floating in the Forth.” Scott describes himself floating away in water, fully clothed, to the sea, only to wrap it up with the line, “I think I’ll save suicide for another day.” Despite the dropping the “s” word, a casual listener could chalk these lyrics up to musical theatrics: emo dramatics. At this point the listener knows (or should know) that Frightened Rabbit is big on drama.

The worry, however, begins to truly set in on the next album: The Winter of Mixed Drinks. The darkness and death obsession present in the first two songs on this album was so troublesome that I quit listening to Frightened Rabbit altogether. Actually, I quit listening for years.

This is nothing unusual for me. As a listener I sometimes drop a band on a casual, instinctual basis. Sometimes I fall into the myopic, almost fickle view that a band I’ve previously loved has peaked and is no longer worth a listen, or that they have taken a fatal wrong turn with their sound—as if a band could never grow and develop and perhaps become something else, something equally, or, surpassingly, great. For the most part I’ve appreciated this selfishness/shortsightedness from my own self. Many times, I’ve been proven wrong to quit on an artist or a band and relished eating crow as I come back years later to feast upon their latest creation with a refreshed and renewed vigor. Wilco, for example. I stopped listening after A Ghost is Born, skipped the next two and came back much later to really enjoy The Whole Love, and to a slightly lesser degree Star Wars, and look forward to appreciating Sky Blue Sky at some point in retrospect, instead of hating it at the time of release because its’ earlier siblings were so majestic and complex.

For the most part I’ve been glad of this impulsive fickleness. With Frightened Rabbit, however, the feelings are deeper and more complicated.

(The conclusion of this essay will run next Thursday, August 1.)

Photo Credit (FR banner): Dan Massie

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is a toll-free number 800-273-TALK (8255). Crisis Text Line offers free help for those who are having a mental health crisis. Text HOME to 741741. Services are available 24/7.

Additional resources are available online here.

Additionally,Tiny Changes, a charity registered in Scotland and created by the Hutchison family offers additional information and support via outreach programs. They are accepting donations of any amount to fund their good work.