I first saw The Blue Nile’s name on Over the Rhine’s old website. Months, probably years, of Linford Detweiler’s archived letters, mini-essays and ramblings lay tucked away in that pre-Facebook corner of the internet.

On one occasion, Karin and Linford saw fit to compile a semi-exhaustive list of albums, movies, and books they found important—works that ostensibly influenced their music. This was gold to me: a who’s who of layered modern and classic artists and writers good enough for their names to ring bells in the hearts of my heroes. I pored over it, making mental notes to myself to investigate every gem in this curriculum.

Limned against poets and painters and great American novelists was this curious name: The Blue Nile. It didn’t sound like Africa, even with the alluvial reference; it reminded me more of a night club, a place full of clinking glasses and cigarette holders, where lengthy, restrained conversations unrolled between the bartender and a ragged anti-hero hovering over a gin and tonic. Also, it felt familiar, like something that was enough a part of the pop lexicon that I had heard once or twice before without knowing what it meant. I did some digging and set about trying to find one of their records.

Amongst a spattering of singles, Paul Buchanan, Robert Bell, and Paul Joseph Moore put out four full-length projects in their extended tenure together. Famously avoiding anything that looked like music industry acumen and occasionally embracing what amounted to de facto failure, they managed to release A Walk Across the Rooftops (1984), the critically acclaimed Hats (1989), Peace at Last (1996), and High (2004).

I’ve always had an aesthetic love for the cityscape in a certain light. Seen through rain on glass windows, the meanest neon glow assumes an otherworldly yearning. Here was music to provide accompaniment for such blue-hour excursions.

The classic Blue Nile sound, or at least the most recognizable, employs countless layers of thick major seventh chords (add sixth, add ninth, add tenth, add twelfth, add is-that-even-an-interval?) coursing out of multiple synthesizer string patches. Beneath this, there are bass lines that may or may not reach the tonic note and lean, architectural, mid-eighties backbeats from the drums. Ethereal piano lofts its voice above the top end, and Paul Buchanan’s powerhouse crooner vocals pierce the darkness with longing.

Their songs subvert the hard rules of pop music. Besides the outlandish stacks of chords and phantom tonic pitches, the verse-chorus-bridge structure gives way to extended jams and oddly placed verses. For some lovely, un-formulaic reason, it works. It really works. The sonic narrative arc of crescendos and decrescendos keeps you moving through the music, especially if you’re driving at night on some lonesome concrete expanse overlooking the cheery lights of cafes and speakeasies. I’ve always had an aesthetic love for the cityscape in a certain light. Seen through rain on glass windows, the meanest neon glow assumes an otherworldly yearning. Here was music to provide accompaniment for such blue-hour excursions.

The first album I found was not The Blue Nile's most essential, strictly speaking. It was the third full-length, Peace at Last, languishing away at McKay’s in West Knoxville for an insulting 68 cents. I remember looking at the sparse liner notes, wondering if Paul Buchanan was blind after seeing a picture of him wearing shades and holding someone’s hand while walking down a country lane. The opening strains of “Happiness” held my attention with Paul’s unassuming acoustic guitar and the ambient tapping of a worn shoe sole on a bare floor:

Now that I’ve found peace at last,

Tell me, Jesus, will it last?

The birds are laughing in the trees.

It’s only make-believe;

It’s only love.

— “Happiness,” Peace at Last

The track slowly wrapped the acoustic in subtle synths and electric guitar, working its way to a surprising gospel choir at the end. Eighties-style synth-pop with a gospel choir? I was hooked. The rest of the record leaned heavily on the acoustic as well, though it never fully stepped into its chronology of a mid-nineties release, preferring instead to be what it was and nothing more.

When I go to record stores, I keep a running mental list of albums I’m hunting. Buying them online isn’t good enough. Perhaps it’s too easy. I want to find them squashed between Pat Benatar and Cars castoffs in a dog-eared box labeled by a part-time dropout who couldn’t care less. I suppose the resurrection element of finding hidden treasures is part of the draw. Consequently, it was only after months of sporadic store shelf rummaging that I found my second purchase. Hats, The Blue Nile’s seminal record, was misfiled amongst the Blue Oyster Cult stack. Again, it was marked by the pejorative 68 cent McKay’s sticker. As with every exciting music purchase, I popped it into the car stereo for the drive home.

If Peace at Last had been an exquisite first sip, Hats was utter baptism by immersion. The reverb-laden snare drum opening “Over the Hillside” set the stage perfectly for the pensive, urban evening:

Working night and day, I try to get ahead,

But I don’t get ahead this way.

Working night and day, The railroad and the fence,

Watch the train go rolling ‘round the bend.

— “Over the Hillside,” Hats

The album cemented Buchanan as a great writer in my mind. The longing evoked by the lyrics and embodied by his voice is brought to bear on the listener through vignettes:

The cigarettes, the magazines,

All stacked up in the rain

There doesn’t seem to be a funny side.

— “From a Late Night Train,” Hats

Buchanan sings about “headlights on parade” and a “love that shines, out among the neon signs.” They are often only sentence fragments, but they populate the setting with details more descriptive of the singer’s feelings than any plainspoken declaration. These lyrical photographs give the effect of staring at Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks:

A girl leans on the jukebox In a pair of old blue jeans,

Says, “I live here, but I don’t really live anywhere,

Because of Toledo."

— “Because of Toledo,” High

When I first heard of their band, Buchanan, Bell, and Moore were in the process of releasing what would turn out to be their final album together. High completed the quartet of records with a front cover that even further encapsulated the wistful, metropolitan feel of the music. A bokeh-style photograph of skyscrapers, shot with a deep yellow filter, introduced the listener to collection of tracks that were supposed to return to the critical success of Hats. I wanted the new project, but I did not find it for a number of years.

My friend Lizz used to live on Roseangle in Dundee, Scotland, in an ornate, gray flat overlooking the broad neck of the Tay River. While visiting friends in the city, I’d walk from Lizz’s toward the Nethergate and City Centre, meandering up the hillside through a tangle of overlaid streets. My path always led past a record store called Groucho’s. Fronting it was a red facade that demarcated the border between the university district and downtown. If I had time, I’d browse their racks for interesting finds, always persistently looking for anything by The Blue Nile. I figured that, as I was in Scotland, a few hours’ drive from the band’s hometown of Glasgow, there had to be more chance of a record turning up in a local store. After a number of fruitless visits, my persistence was rewarded with a copy of High, hand-labeled with a scuffed sticker and a spidery pound sign. It was missing the liner notes, but I didn’t care. I had found it.

I had no car, so I played it in my friend Bruce’s stereo at his house on the north side of the city. I stood there, listening, scanning Bruce’s books on Celtic Christianity and his Radiohead records:

She lives in a house in London;

She lives in a house in town.

Waiting to greet the children,

She sits around in her dressing gown. Are these the days?

— “The Days of Our Lives,” High

The only two things I bought on that trip, other than food, were a necklace for my wife and High. My wife isn’t one for much jewelry these days, but that record still takes a spin in my car on a regular basis. Its continued blend of confessional and still-life lyricism is perfectly accompanied by a return to the synth-ballad sound of Hats, though with a darker, more worldly tone.

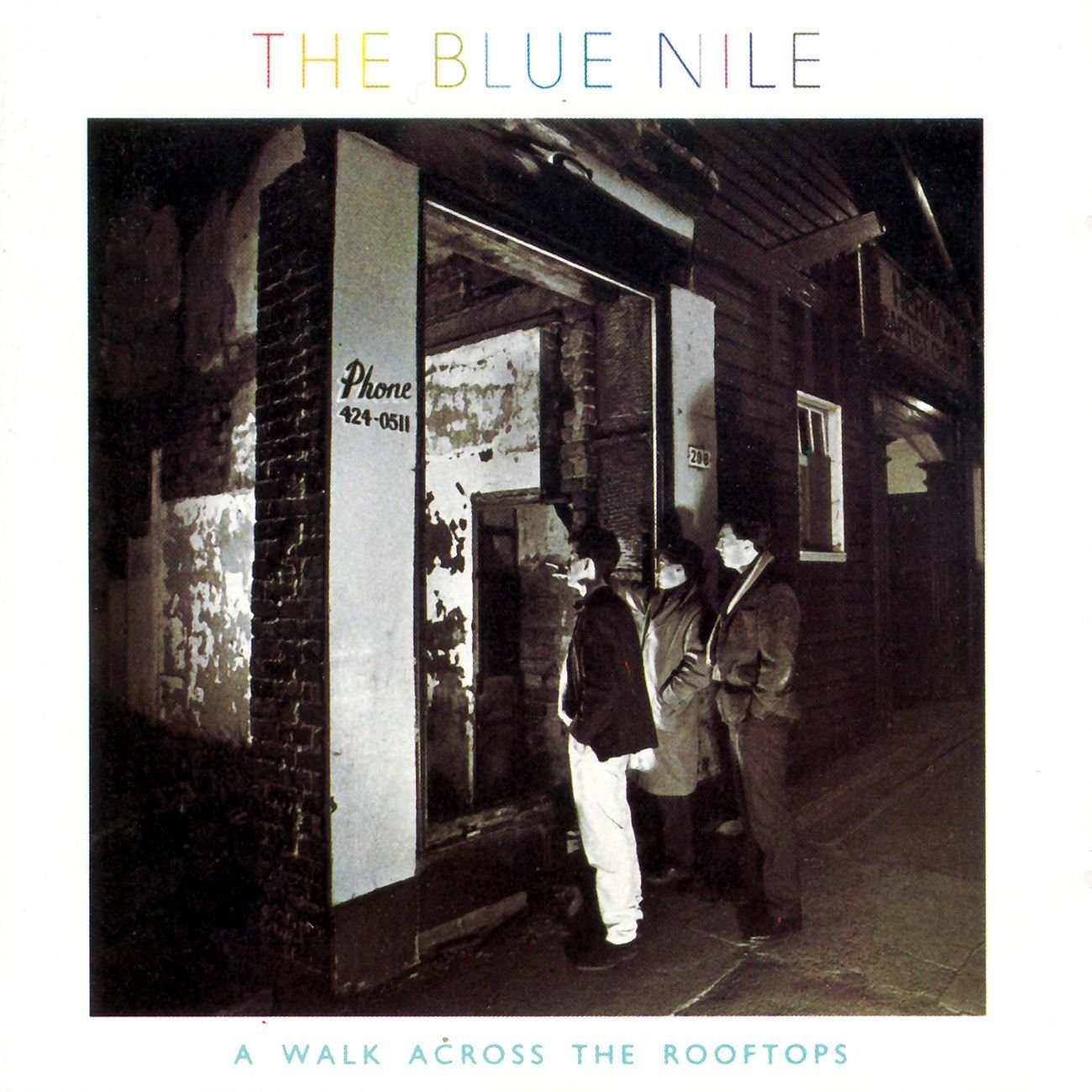

The last album I found was the band’s debut effort, A Walk Across the Rooftops. It’s legendary, in a sense—heralded by the spurious tale that an electronics outfit called Linn Products formed a record company in 1984 solely to release it. Though the rumor has since been dispelled, it still inhabits the mythos of The Blue Nile’s genesis for me. The raw excellence of their musicianship pairs with palpable joy and a solid sense of place:

I walk across the rooftops,

The jangle of Saint Stephen’s bells,

The telephone that rings all night,

Incommunicado I am in love;

I am in love with you.

— “A Walk Across the Rooftops,” A Walk Across the Rooftops

The line of traffic comes to a standstill

For the Love King, out in the morning air.

I find the place I started from.

The wild is calling;

This time, I follow; Easter parade.

— “Easter Parade,” A Walk Across the Rooftops

The loveliness and wonder of The Blue Nile’s music isn’t all immediately apparent, even for those who love the style. The wandering song structure and mountainous chordal arrangements require committed listenership, but the work, as art, is some of the most beautiful I’ve heard. Truth be told, I probably only made it as far as I did through the band’s catalog because of Over the Rhine’s endorsement—that and a gospel choir tossed into an eighties-style pop record—but it’s a journey I don’t regret in the least.