The hoped-for osmosis worked for Wesley Schultz.

In his earliest days as a performing artist, it wasn't uncommon to find Schultz playing cover songs from Bob Dylan or Bruce Springsteen in a dark club somewhere, mixing in originals and hoping that, in some way, playing songs with such gravity would eventually rub off on him. Substantive songwriting by osmosis.

It's very likely that some burgeoning songwriters are today doing the same thing to Schultz's songs as front man for The Lumineers. After three full-length albums, the Lumineers have toured the world multiple times, topped the charts, and fulfilled several musical dreams. Now on a break thanks in part to a global pandemic, various Lumineers have turned their attention inward to personal interests in order to find their next creative project.

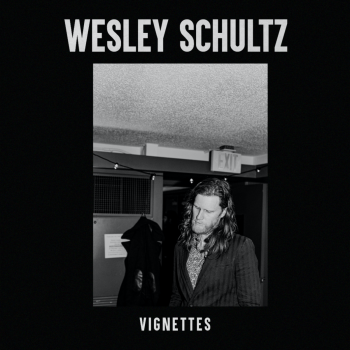

Vignettes is the latest release from Schultz, a Simone Felice-produced project intended to honor some songwriting heroes and return to the influences of those nascent performances.

Analogue: I read your words about this new album reminding you of your earliest days playing covers in solo sets. Do you miss those days?

Wesley Schultz: Overall, I'd say those days are mixed. I think a lot of good music comes out of strife or struggle or reaching for something that is not even close to being promised; it's a pipe dream. I guess a good way to look at it is that these songs were the songs I wish I'd written while I was playing these bars. I remember playing my own music and then playing these covers and that the reaction was just so different at the time. These songs had a weight to them that you just couldn't pretend wasn't there.

"It was almost like you're trying to get it by osmosis. You're trying to absorb it in some way."

There's a ledge you step off of when you decide you're not going to play any more covers. This was before that little leap took place, but I remember playing "My City of Ruins". It started off in college, I'd play covers for two or three hours mixed in with my own. Then I eventually moved to the city, and I'd play Bob Dylan or Bruce Springsteen or even "Come Pick Me Up," that Ryan Adams song, and I'm almost sure a lot of people didn't know that Ryan Adams song, but they knew it was good. It felt like there was something in it that I wasn't getting, that I wasn't doing as a songwriter yet.

So in a way, they were these things that seem so unreachable but they were also playable. You could play them. You just couldn't write them. [Laughs] It became this skeleton or road map of like, 'Hey if you want to make music people will listen to, these are some examples.' It was almost like you're trying to get it by osmosis. You're trying to absorb it in some way. I've heard someone say that what you consume, you emit. I think that's part of why songwriters learn a lot of other people's music. I've heard other people talk about writing itself and they type out or handwrite passages of other people's writing and getting that into your bloodstream somehow. So I think a lot of these covers represent what felt insane at the time.

I've had this CD jewel case I gave to my dad 20 years ago and it's all covers with four originals, because I'd just started writing music. Some of these artists I've met, which is crazy. Like I'm looking at Dave Matthews, and we opened for him and got to meet him. Tom Petty, I met him. There's Pearl Jam, and I've met Eddie Vedder. All these people who I thought were super heroes and some of them I've shook their hand through music. So I've made progress with it. Maybe there's a kid out there covering our music, but it is crazy because it does feel like just yesterday. It's like survivor's guilt or something where you still don't understand why you are where you're at.

Analogue: You mentioned the word "yet" in terms of songwriting excellence or having that weight that those early covers held. What was the first song you remember writing that had that substance or heft to it?

Wesley: I remember writing "Flowers in Your Hair". I was in this Bushwick apartment in Brooklyn. All the blinds were closed because we're on the first level and there's all this chaos outside. So we had these thick blinds that blocked out all the light. It's like being in a casino; you never knew what time of day it was. Then "Flowers in Your Hair" was the first one to trickle out and there was a car alarm going off in the voice memo I made. We liked it so much that we kind of used that idea and sound in the recording. I felt like it spiralled from there, because that poured out and then "Ho Hey" was right after that and "Life in the City". All these other songs came out of this little shitty apartment.

In the midst of all that, I can't find the video but I definitely did this, but I recorded myself singing "The Ballad of Lou the Welterweight" [by the Felice Brothers] and put it up on YouTube and now it's gone. I don't know what happened. That was 2008 and so right around the same time I was writing these songs, I had discovered the Felice Brothers and was really blown away by their production. It felt like something we were into and that we could do and that we gravitated towards anyway. Then to hear a band we liked doing it and not apologizing for it, it felt like lo-fi production done perfectly.

They had an amazing album called Tonight at the Arizona. So to have that on the record, "The Ballad of Lou the Welterweight," on this one 12 years later and then to have Simon Felice producing the last two Lumineers albums, it's kind of like there was some force, some attraction to some sound that was happening, even in that little apartment that led to this. I don't think it's all by accident.

Analogue: What was the impetus to make a covers record in the first place?

Wesley: Part of it was that I was sitting around doing some livestreams on behalf of the band. Playing our own music, we had three albums out and I was playing those songs a lot. I was looking for a lot of things to do with them during these fundraisers. "My City of Ruins" is one I'd played for a while. "Green Eyes" was one I'd tried to play and enjoyed playing. Things like that set the stage a little bit.

But I think the biggest impetus was randomly a couple years, Simone was part of an Amazon project called Produced By. He said, 'Hey, you wanna do a song?' I said I didn't want to do anything original necessarily because I want to use those ideas for the band. I don't want to take something away from what the main thing is. He said we should look for a cover and we settled on "Bellbottom Blues". He'd showed it to me the night before; it was one of those that had just fallen through the cracks somehow. I was blown away. I heard it one day and the next day we recorded it.

The piano player, David Baron, didn't know the song as well, so he was feeling his way in the dark. We did that and two years passed and then it gets a wider release on Amazon. Simone was listening in his car and he said, 'That's a really good recording. If you want to do it again, I have some free studio time during this quarantine.' I was out there getting into the woods with my family. We did it in the course of four or five days, just a fast process. It all felt really carefree. So the impetus was this genuine, 'Would you wanna do this?' That's the total opposite of a Lumineers record which is listening to a song a million times to make sure we have every instrument right and every moment dialed in.

Jeremiah made his own solo record during this time, so I think we're both taking a lot of this experience to the new record that we're working on. Oddly, it teaches you something about yourself and creativity when you're so used to the way you do things. To do things differently is a good thing. If you're a chef and you're only used to cooking Asian food and an Italian shows you how he cooks, I just think there's something to glean from all these things. So spontaneity and the unplanned and going with that danger, funny things happen and great things happen in that experience. I'm trusting a lot more in the voice memo.

"In the beginning, you have no idea what you're doing. You want to stay innocent in the process. You don't want everything to be safe and planned and in control."

Analogue: What fueled that for you, the lack of trust before?

Wesley: I think having experiences where you record something and you think it's going to change the world literally and you're just so happy with it on a Monday. Then by Wednesday, you think it's the worst thing you've ever heard and it sounds like some Bon Jovi rip-off or something. That literally happened one time. We made this idea. We loved it. We were in Jer's third floor. Then we smoked weed and listened back and I said, 'Oh my god, this sounds like a bad Bon Jovi song.' We can't do this. [Laughs]

It would be like if an actor thought he nailed the take and then went back to watch the footage and it was completely different than what he thought. So some part of it is also probably that you do it enough, you can be free and you can express because you have a grip on what you're doing. In the beginning, you have no idea what you're doing. You want to stay innocent in the process. You don't want everything to be safe and planned and in control.

I heard Michael Stipe talking about creativity and how he makes music as a circle. At the beginning you're at the top of that circle and then you're at the bottom in this sweet spot where you have craft and instinct and they're mixing really well. But at some point, you overly craft it and you have to return to not knowing what you're doing again. Making Vignettes was a return to that. I couldn't have made it five years ago because I just don't think I was there. But in between there's been a lot of writing and a lot of recording to where I can be a little more free about it.

Analogue: Bit of a personal question, but the new record has "Mrs. Potter's Lullaby" on it and I'm a lifelong Counting Crows fan. Love what you did with it, but it's not the most obvious cover just given its length.

Wesley: I adore that song. I think the lyrics are brilliant and Adam Duritz... I don't know if it's fair to even say he's underrated. He's just such a great lyricist. I remember annoying my friends because I would play that song so many times in a row when we were drinking together. I'd say, 'Listen to this line! Listen to this line! And then this one!' [Laughs] I'm the annoying friend hitting you on the shoulder singing over the words.

That's a song I'd never touched. I never covered it in a bar. I only listened as a fan. When it came time to make this covers record, I thought, 'Man, I've always really loved this song.' One of the things I'd always loved about it is that it became accidentally sort of a b-side or a lesser known track and I always thought it was the summit, that it should have been bigger. I was trying to expose the song that was there the whole time. Maybe it was the context. Maybe it was the songs around it on the album, but I always felt like it was such an underrated, incredible song. You're lucky to have that song, if you're me, because you already know it's good and you can surprise some people with it.

Analogue: What's your cutting room floor on a project like this?

Wesley: Not too deep. On a Lumineers album, we've got a lot of sawdust on the floor. I think there were two songs on this one: a Cars' song called "Drive" and then Billy Joel's "She's Always a Woman". I love the Cars and grew up listening to them with my dad on every road trip. I knew I wanted to do it but once I sat down to do it, one thing I learned about the Cars or at least that song, if you remove the synth from the instrumentation, it's so one with the music that you're taking something vital away. So the way we were approaching these songs didn't work on that one. You couldn't take that much away. It didn't make sense. That's part of the genius of the way they write songs.