The goal was to make the songs shine.

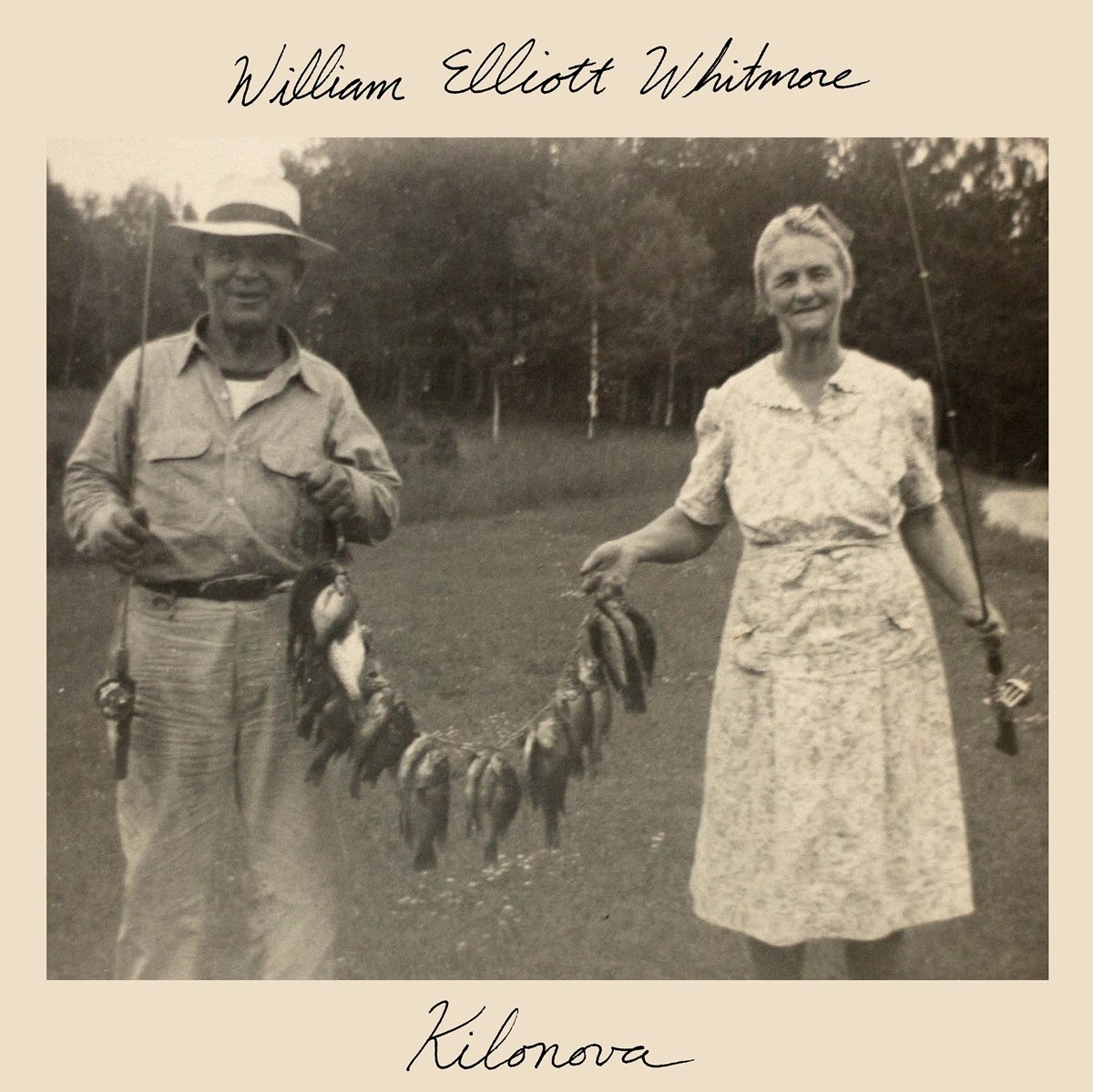

For the last 15-or-so years, William Elliot Whitmore has proven himself to be a songwriter's songwriter, as they say, a thoughtful artist whose attention to his songcraft sets him apart from one album to the next—a sum total of six studio LPs that have garnered loads of critical acclaim. For his latest album, his seventh, Whitmore decided to turn the tables and tip his hat to those who have championed the craft in a similar way.

Kilonova is the end result, a brilliantly pared down selection of varied favorites of Whitmore—with titles from The Magnetic Fields and Bad Religion, Johnny Cash and Bill Withers. The songs are personal favorites, but the common thread had a single mission in mind: to make the songs shine. If Whitmore thought he couldn't enhance the song in some way, he would leave it alone (unfortunately for a John Prine tune).

The remaining ten selections not only reveal Whitmore's influences but provide an important peek inside his mind to show what he appreciates as a music listener. For an artist already so heralded and held up as a fine example of a songwriter, Kilonova is a deep dive into Whitmore's musical mind. It's also a great mix.

Analogue: I love the way you reinvented the Magnetic Fields song. How do you know what to do with a song like that?

William: I was so excited about that song, because I love Stephin Merritt’s songwriting so much. They’re a great example of a band that you either know them or don’t, but if you know them, you love them. They’re not a household name, necessarily, but the people that love them, they love them. It’s like The Mountain Goats or something, who I love as well.

I’ve loved their stuff for so long, and I knew I wanted this song to be the first track because I was so proud of how it came out. I’ve loved this song for a long time. It’s off an album called The Charm of the Highway Strip, and it’s like a lot of road songs. I feel like he must have written it when they were on the road a lot. I thought, 'Man, this song sounds like a folk song to me.' Which a lot of his stuff would be really easy to do a folk version of, which I’m sure tons of people have.

I just love the story it tells. The first few times I heard it, it really invoked an emotional response in me that is hard to explain, but the imagery in the song just kills me. I think of a young native girl and everything that’s ever been wrong is because of trains. It just kills me.

I’ve known for a long time that I wanted to record it. A lot of these songs, I’ve been covering them live for years as I’ve said, but I thought I’ll do the easy thing and just make it into a little folk song. Merritt actually does the daring thing, which is none of the songs on that album... they barely have guitars. It’s all synths and drum beats and weird instruments. That’s the daring thing; I did the simple thing. I took the easy way out and just said, 'Hey, how about just an acoustic?'

I don’t know if I made it better or worse, but that’s what I do, so that’s what I did. So I just think, 'God, I almost hope he never hears it,' because he’d go, 'Well yeah, you did the obvious thing.' I don’t know. But maybe I overthink shit or whatever.I don’t know if you know that record that well, but his arrangements are really unorthodox. And he could have just had it been guitar and drums and bass and whatever, but nope, it’s all like he did it in his bedroom and made it really original.

But the lyrics still remain to me like a folk song. So I knew I wanted to lead out with that, especially right now with our current political climate.

Analogue: Do you have a philosophy on handling that side?

William: I do have political songs. I try not to hit people over the head with stuff. I don’t stand on a soapbox with stuff, but I have my views and my thoughts, and I have some songs that are more political than others. But what he did with that one... you sort of hide the medicine inside the candy a little bit and it makes you think. I thought right now would be a good time to have that be the first track.

Analogue: I think the beauty of your album is that these unexpected songs are given these stripped down treatments where they find a vibrant, new life. You're shining these great lights in all directions. Was that a goal for you?

William: Yeah. That’s great. I’m glad you’ve picked up on that. I have that same problem, too, where certain songs I’ll hear and I’m really analytical of music, but it might take like 20 listens to go, 'Oh that’s what he’s saying there.' It’s kind of low in the mix. I didn’t know what he was saying, especially that song, "Fear of Trains." I feel like maybe he was self-conscious about his vocals or something, because they’re really low in the mix. I always thought, 'Man, if I had mixed this record, I would bump those vocals up and make them shine, because lyrics are his whole thing.

I’m just supposing, but I feel like he was like, 'No, bury the vocals because I’m not a great singer. Or I just picture him being self-deprecating. But I would say, 'No, you wrote these beautiful things. Bump them vocals up so everyone can hear what you’re saying.' With every song on this record, to different degrees, I really wanted to make them shine. Let’s strip away everything, or strip away a lot, which is what I do anyway.

The Bad Religion song—"Don’t Pray On Me"—is another example. The original version is really fast. It’s what they do. It’s really fast, it’s awesome, but yeah it’s like I want to take that all away so you just hear the lyrics and make it really sparse. I actually had some high praise with that one. Brett Gurewitz from Bad Religion wrote that song. Years ago I covered it for some other thing, and he said he really liked it. He said he always thought of Bad Religion songs that he was writing as folk songs. They would just speed them up, which anyone knows that that’s all punk is—it’s just folk, blues, country sped up. Three chords and simple melodies and stuff.

I just thought that was a little feather in my cap, because he’s like, 'Man I really liked that. You stripped away the ostentatiousness and brought it back down to what I always thought it was, which was a folk song.' So when I’m feeling down and out and in the dark places, I remember things like that where that was praise from Caesar, man. Brett Gurewitz.

But yeah, to your point, stripping away things. A song like "Ain’t No Sunshine" has been covered to death. I didn’t realize it, really, because I’ve just always loved Bill Withers. This is one of those songs that’s been covered by almost everybody. But you know what? That’s okay. I want to throw my hat in the ring. And there will be certain fans of mine that haven’t heard the other ones. That’s one I changed very little. The arrangement is pretty much just like Bill Withers. The original is so stripped down, and that’s why he’s great. That I almost did one for one.

Overall I just wanted to take everything away and focus on the lyrics. Hopefully people will go back and go, 'Man I should listen to more Magnetic Fields or Harlan Howard or Jimmy Driftwood or Captain Beefheart. Because that’s what I’ve done in the past. That’s the hope.

Analogue: What does the cutting room floor look like on something like this, or is there even one? Do you find that some covers end up not working out so well?

William: Yeah. That’s a good question. It was pretty curated. In other words, I knew what I wanted to go on it, pretty much, but there was a little back and forth with a few other songs that I just didn’t think I could give them their just due, their just desserts. One of them, for example, was a John Prine song. He’s another to add to the list of greatest songwriters of all time. That’s what we’re all chasing. We’re all trying to keep up with him. I’ll try to write a song and then like, 'Shit, he got there first, man. Damn, he’s already got a song like that.' He’s amazing.

But he had a song, one of his famous ones is called "Sam Stone." It’s about a Vietnam vet coming home, or at any rate a veteran of a foreign war coming home, and his name’s Sam Stone. He gets addicted to drugs. He’s got PTSD, which they didn’t even call it that back then. They probably just called it shell shock or whatever. It’s a very touching, beautiful song about this poor guy. I just though, 'Oh man, people aren’t writing stuff like that,' and so that was one that I thought would be cool to put on the album. But I realized I couldn’t give it what it needed. I don’t even know how to tell you what that means. It’s so beautiful I can’t touch it. Again, I don’t know what that line is in my mind of what’s okay and what’s not. So that ended up not going on.

But it was really fun thinking of the ones I did want put on. That was a lot of fun. It’s like making a mixtape, where you curate something for your buddies or a girl you like. It’s so much fun. So this is an example of that on a larger scale. I’m going to put this list together for everyone. It was a lot of fun.

Analogue: Do you remember the very first cover you performed live?

William: Let’s see. I started playing guitar and singing earnestly when I was in high school. This would have been the early '90s. It was a small little country school, but all the little towns in the county kind of congregated to this one school out in the middle of a cornfield pretty much. I would bring my acoustic guitar to school and during lunch would sit around and play in the hallway and stuff. There was a few of us that would do that.

I’m sure it was something off Nirvana Unplugged. Being a kid and being around all the country music, then you get into high school and you’re starting to hear about bands like Soundgarden and Pearl Jam and Nirvana. You're like, 'This is my music.' At that time, I still loved Johnny Cash, Hank Williams, and Charlie Pride, but there's a special time in your life when you find your own thing.

That was just a cool time in music. I’m pretty sure the song was probably "The Man Who Sold The World," another cover by the way, now that I’m thinking about it. Kurt Cobain covers this David Bowie song. I didn’t even know David Bowie that much. That made me go, 'This guy David Bowie must be pretty cool.' That’s how country sheltered I was. I mean, I heard David Bowie a little, but wow, what a beautiful song. Here this guy strips it down and makes it new. That was an example of a great cover. Anyway, I’m sure it was something like that.