By 1998 I was a senior in high school and my musical tastes were only starting to coalesce.

In that awkward bubble of teenage identity, I tried (publicly) to listen to the most obnoxious, abrasive music I could: The Melvins, The Velvet Underground, Kyuss. Privately, however, I swooned to Counting Crows, PJ Harvey, the Gin Blossoms—anything with a melody and two guitars. How does the saying go? “I was young and foolish then, I feel old and foolish now.”

1998 was also the year I read Robert Christgau's Rolling Stone review of Car Wheels on a Gravel Road. I had never heard of Ms. Williams' before, but Christgau's four-star review was effusive, enthusiastic, and heaped so much praise upon the album, I bumped it to the top of my ‘To Buy’ list. Later that year, after my initial purchase, I will suggest it isn’t inaccurate to say Car Wheels On a Gravel Road changed my life. It was the tipping point I needed to leap into the realm of meaningful music.

Listening along in my bedroom or in the car, I couldn't quite grasp the clarity of sounds coming out of my speakers; the 12-string electric guitar, the country/blues fusion, and that voice. Her voice. It was like hearing my heart beat for the first time and wholly understanding its purpose; it felt like a blood transfusion and, more importantly, it sounded like Heaven. "God," I thought, "where did this music come from?" From the South, of course, where all Godly and goodly things are born. I’m a Southern boy and I discovered I spoke the same language as Ms Williams—but she sang it better than anyone.

If someone gets to take us by the hand and usher us through the shadows to get to the light, please God, let it always be Lucinda Williams.

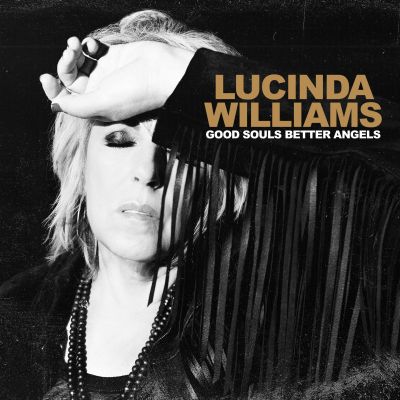

Ms. Williams and I have spent many more years together in song. Her voice is a balm in troubled times, her words always land with the utmost clarity. In the years after Car Wheels, her prolific songwriting became even more direct and meaningful, communicating through song what most of us have trouble admitting to ourselves. Every Lucinda Williams album is a jewel, but Good Souls Better Angels, her latest album released on her own label, is her best record since Car Wheels On a Gravel Road.

Good Souls Better Angels finds its roots in the deep, dark soil of the Southern blues, planting a shovel in bloody ground and digging up bodies. It’s a dark and timely record, but it’s also a record that doesn't apologize for asking us to confront societal darkness and our demons. If someone gets to take us by the hand and usher us through the shadows to get to the light, please God, let it always be Lucinda Williams. I’d follow her honeyed Southern drawl anywhere, down to the deepest well.

A quick skim of the songs titles on Good Souls points to an exploration of troubled years. “Bad News Blues,” “Man Without a Soul,” “Pray the Devil,” and “Big Black Train” make it sound like the road to Hell is paved with all manner of grime and “all the news you can read / all the news that’s fit to print." But like The Clash or Nick Cave before her, Williams figures that if you have to confront the devil, you may as well bring some songs that can pummel your ears while speaking the truth. Might as well play electric blues guitar while the nation burns; it sounds a hell of a lot better than cable news.

Opener “You Can’t Rule Me” slides in on an ominous verse before blowing the doors down with flurry of electric guitar, bass, and drums. “Man I got a right / to talk about what I see / way too much is going wrong / right in front of me / you can’t rule me,” Williams starts. My God, if you don’t feel the stirring of a raised fist after that track, check your pulse.

Similarly “Wakin’ Up," “Down Past the Bottom” (a bluegrass stomper written by Greg Garing but turned inside-out by Williams and her band), and “Big Rotator” stomp and holler their way through topics like domestic abuse, what resides beyond the darkness, and the machinery of the system. But with every song we’re not being dragged down; rather, we are lifted up as Williams lends her voice to the frustration and injustice of a system that no longer seems to care about the people that help it run.

With every song we’re not being dragged down; rather, we are being lifted up as Williams lends her voice to the frustration and injustice of a system that no longer seems to care about the people that help it run.

Amidst the dark Ms. Williams has moments of sweetness and light, also. “Big Black Train," “When the Way Gets Dark,” and closer “Good Souls” are hymns that float out on waves of tremolo guitar, crawling bass lines, and her silvery sweet vocals. “Don’t give up / take my hand / you’re not alone,” she offers on “When the Way Gets Dark.” On paper it sounds reassuring but when given over to Ms Williams, it sounds like the only sentiment worth a damn.

There is no sense attempting to disguise the individual Ms. Williams targets on songs like “Man Without a Soul” and “Bone of Contention.” The former includes karmic rebukes to the man whose names rhymes with "Drump": “You bring nothing good to this world / beyond a web of cheating and stealing / you hide behind your wall of lies / but it’s coming down...How do you think this story ends? / It’s not a matter of how / it’s just a matter of when / ‘cause it’s coming down.”

“Bone of Contention” is pure fire and punk energy, a song Ms. Williams and her band have honed live. “I saw you walking you’re two-headed dog / and you pretend to worship God / mathematics and politics / three sixes and deadly tricks,” she growls and sings before blasting out the chorus: “You’re a bone of contention / you’re a thorn in my side / you’re the salt in my wound.” I heard this song when Ms. Williams toured alongside Drive-By Truckers, and, in case the meaning was at all unclear, after the song was through, Ms Williams proclaimed, “Maybe we should cut that song and send a few copies to the White House.” (Side note: If I were on the receiving end of a song-lashing like “Bone of Contention” I would seriously consider moving to a monastery for some deep self-reflection, but I guess that's the point.)

Everything—everything—about Good Souls Better Angels is exquisitely recorded, calibrated, and presented for maximum effect. The band—guitarist Stuart Mathis, bassist David Sutton, and drummer Butch Norton who together they form the band Buick 6—is on fire. They swing, shuffle and rock whenever the songs call for it, doling out simple, spare accompaniment for ballads; locked-in precision for blues and country riffs; and high-dollar rock and roll flair for everything else. Their synchronicity gives Ms. Williams room to maneuver her voice and guitar through the depth of the songs. Her voice is pushed in close to the microphone, warmly analog and perfectly balanced with the surroundings. Even the sequencing of the record is a thing of beauty. The rockers are spaced between the slower numbers and the album dips in and out of the murk to come up for sunlight and air after the darker moments. It's a journey from beginning to end.

Like Bob Dylan or Leonard Cohen, Ms. Williams confronts the struggle for morality and righteousness with her pen while keeping an eye on our mortality.

Like Bob Dylan or Leonard Cohen, Ms. Williams confronts the struggle for morality and righteousness with her pen while keeping an eye on our mortality. Dylan and Cohen both released late-era albums addressing a nebulous oncoming darkness and, should you look for them, it’s not difficult to spot similarities between Good Souls Better Angels, Dylan’s 1997 album, Time Out of Mind, or Cohen’s final album, You Want It Darker. The sense of peering through the shadows and watching the world become an unknowable place without known order permeates everyone of these records. But they’re also personal, poignant, and deeply humanistic works. When Dylan sang, “It’s not dark yet but it’s getting there” on “Not Dark Yet,” we couldn’t know then what we know now—that the darkness was decades away. A version of it is here now, but Ms. Williams can help burn it off. Just follow her voice; she won’t lead you astray.

All photos by Danny Clinch.