[Ed. Note: The following essay discusses suicide and drug use and may be sensitive to some readers. Please be advised.]

You can read Part 1 of "When A Stranger Dies" here.

In the early part of Frightened Rabbit’s third album, The Winter of Mixed Drinks, my emotions were stirred up to palpable revulsion mainly due to the song “Swim Until You Can’t See Land.”

Not only did the eponymous chorus strike me as dangerous mantra for the singer to sing every night, it struck me as a possibly problematic phrase to have people sing along with. At worst, it sounded like a possible exhortation for the listeners. If you swim until you can’t see land, it's not the swim out that kills you, it’s the attempt to find land once you have done so. I worried that the uplift of the music could romanticize the actions entailed. If these were dramatics, they were dangerous ones. And they troubled and angered me.

Here we crash up against the metaphorical wall that exists in art. Did I believe Scott wanted people to swim until they lost orientation? Of course not. Did I believe Scott contemplated or wanted such a fate for his own self? I didn’t then. I just worried at possibly overwrought lyrics being misconstrued. I barely listened through a few more tracks on The Winter of Mixed Drinks as “Swim Until You Can’t See Land” became the morsel of food to ruin the meal. I stopped listening; I stopped trying.

The year was 2010. Strangely enough, I caught up with F’rabbit (as they are sometimes called) mid last year as the same friend who originally introduced me to Scott and co. many years ago seemed slightly amused that I had given them up. He recommended checking out the album I never made it to, Pedestrian Verse. The most recent album to come out was Painting of Panic Attack and I really had never given The Winter of Mixed Drinks its fair shake, but he said to return to the album sandwiched in between. And my friend was right.

I was back in it quickly. The emotion was there as if it never was gone at all. Pedestrian Verse brought the same power but was different as well. It was like the aftermath of a seismic argument in a relationship; when you make up, the love is tuned to the same frequency but the wavelength is different. Neither better nor worse but perhaps a little more resilient and more complex.

The songs on Pedestrian Verse represent a growth for the band as a whole, both emotionally and musically. There is a sense that Scott and the boys are trying to expand their palate as the sonics and the instrumentation manage to be catchy but with added depth and texture. Scott retains his knack with melody and intensity of emotion but manages to expand his sadness beyond himself. He spins pathos into empathy. The “I” is there in his songs but less frequently. And, as often as not, when it is there it feels like a character he is offering up; a suffering, problematic, broken individual that is not him, or you, or the people you know, but us.

Perhaps it was a release for Scott to write in the guise of another person in despair instead of the person he was. On the first track “Acts of Man” he preemptively takes all the flack of the #MeToo movement onto his shoulders by becoming the acts he deplores. He is the “dickhead” getting a girl drunk to take advantage of her, he is the “knight in shitty armor” taking full advantage of the drunken girl. Maybe Scott had these people within him, maybe we all have the worst “acts of man,” or woman, dormant inside us, and, like Scott, we are “not heroic, but we try” to be. Maybe the awareness of these possibilities within him was part of his personal issues. “Acts of Man" is a song of rage but it’s a rage that comes from a certain recognition.

If not all the “I’s” on this album are necessarily Scott speaking, the final song, “The Oil Slick,” certainly drops any such artifice. When Scott sings “Took to the ocean, in a boat this time, only an idiot would swim through the shit I write,” it’s a clear self recrimination, one I even sadly enjoyed at the time because I saw it as a disavowal of the dangerously depressed Scott of "Swim Until You Can’t See Land.”

Don’t hate on people that love someone they’ve never met. Don’t hate on yourself for loving someone you’ve never met. Love is one of the better options.

Months later I had listened to Painting of a Panic Attack a good amount and even dipped my a toe back into The Winter of Mixed Drinks when I heard via the internet that Scott was missing. Bewildered briefly, I surely knew, as many likely knew, when they heard. We knew what we didn’t want to know, didn’t want to believe. The last two tweets from Scott had gone out a half day before I heard of his disappearance.

"Be so good to everyone you love. It’s not a given. I’m so annoyed that it’s not. I didn’t live by that standard and it kills me. Please, hug your loved ones."And then:

“I’m away now. Thanks.”

Scott’s body was pulled from the waters of the Forth River a day after he went missing—waters he sang about floating away upon in the final song of the second album.

This is where my feelings of, essentially, rage-quitting Frightened Rabbit many years before, get complicated. Is it insane to feel guilty? Like I let him down?

Obviously, it is silly and a bit ridiculous. Obviously, me not listening to or buying Scott’s music for four or five years had little to no impact on the man. Whether you view my mild protest as action or inaction in my life, it didn’t even register at all in the life of Scott Hutchison. Yet the sad feeling that I didn’t do enough is there. How can this be? He was a person that I loved, enjoyed his musical company, saw in him what I sometimes saw in myself, and also appreciated our differences. He was a total stranger. He was my friend.

Perhaps it was a release for Scott to write in the guise of another person in despair instead of the person he was.

Near as I can tell there are two reasons for this feeling of ghost connection. The first I already mentioned: Scott’s music yearned in every line for closeness and connection. As artistically crafted as his lyrics and melodies were there was little artifice in either. The most abstraction and obfuscation he could summon was to write as a character that was just as lost, lonely and forlorn as he, merely from different circumstances. If you listened to Frightened Rabbit and you got it, you understood Scott. He wanted you to. He wanted to connect. His music demanded it.

The other reason I think I have cried for strangers like Scott, Bowie and Bourdain is equally, if not more, complicated.

This experience is not completely new. Cultural figures passing having an emotional impact on a participant of said culture surely isn’t confined to the 20th and 21st centuries but it does seem to have grown in reach and power therein. In the times when regents and authority figures were little more than a name and, at most, a face on a coin, their passing couldn’t mean more than some worry over your land or kingdom’s stability. Skip forward to the funeral for Princess Diana, however, and you'll find masses of people who never knew her, yet felt forced to tears by her loss.

Of course their reasons for crying are distinctly nuanced but without the access granted through photos, interviews and television appearances, the connection these people felt (whether one-sided or not) would have been impossible. With the internet and all-hours-access to content, it is even more possible to connect and spend copious amounts of time with people you’ve never met. You can and maybe do spend as much time in the company of strangers as people IRL.

Scott said it best: "Be so good to everyone you love."

Last year people on various platforms bemoaned the multitude of celebrity deaths. Many wondered at the surprising number of them but it makes sense as our systems of connection become greater, stronger, and faster, that we meet and become attached to more and more people of societal renown. And, I believe, this phenomenon will only get worse.

Our oldest gateway for this one-way link, the cinema, is roughly 90 years old, the television is reaching its seventies. The true age of the internet is approaching the end of its twenties, but it has already shown an exponentially more powerful ability to connect. It is only possible that as our conduits of mass culture grow in reach and content, then consequently grow in age, we will witness more of our cultural friends and family members passing—and more often. We will watch our chosen family, our family from afar, grow old and die just the same as our genetically chosen family. Is it wrong to feel more attached to Betty White than your real grandmother? I’m sure it depends on your personal G-mom, but I would argue that no, no it isn’t wrong.

Perhaps another reason I feel guilty about Scott is because I got so much from him but I could never give him anything back. Of course I bought some albums and a ticket to that one show, but no amount of whatever coin made it back to his pocket can be considered ‘compensation' for what Scott gave me.

Truth is I feel like I knew Scott. I didn’t really—not anymore than I knew Bowie or Bourdain—but I did. It’s why I call him by his first name in this article. Bowie gave me a template for how to except myself, Bourdain was the wise, and cantankerous uncle I never truly had, but Scott was… my friend? A compatriot? His music, his art, wanted honesty and wanted to be heard. Maybe that’s why it hurts so much I turned my ear away for a while. He wanted me to hear what I couldn’t, what I wouldn’t. I felt uncomfortable with his dark thoughts, maybe because they mimicked my own at my darkest. Maybe it was too much. And I wasn’t strong enough. I was, and am, angry at Scott for letting the darkness cut so deep into himself, and angry at myself for not being able to listen to a friend as he confessed, as he made a gift of his darkness into song and all he wanted, all he had ever asked of me, was for me to hear him.

When all is said and done I could never really understand the sorrow and the other emotions of those that truly knew Scott: his Brother, his lovers, his friends. But I knew him, in a way. In a way that is surely only important to me but that is importance nonetheless.

I got so much from [Scott] but I could never give him anything back.

Don’t hate on people that love someone they’ve never met. Don’t hate on yourself for loving someone you’ve never met. Love is one of the better options. Love yourself and other people because we are all David Bowie, because we are all malleable and exotic space travelers. Love humanity in the way Bourdain did: skeptically, whole-heartedly and without compromise. Please do your best to listen to those close to you even when it is difficult to hear what they have to say.

Scott said it best: "Be so good to everyone you love."

***

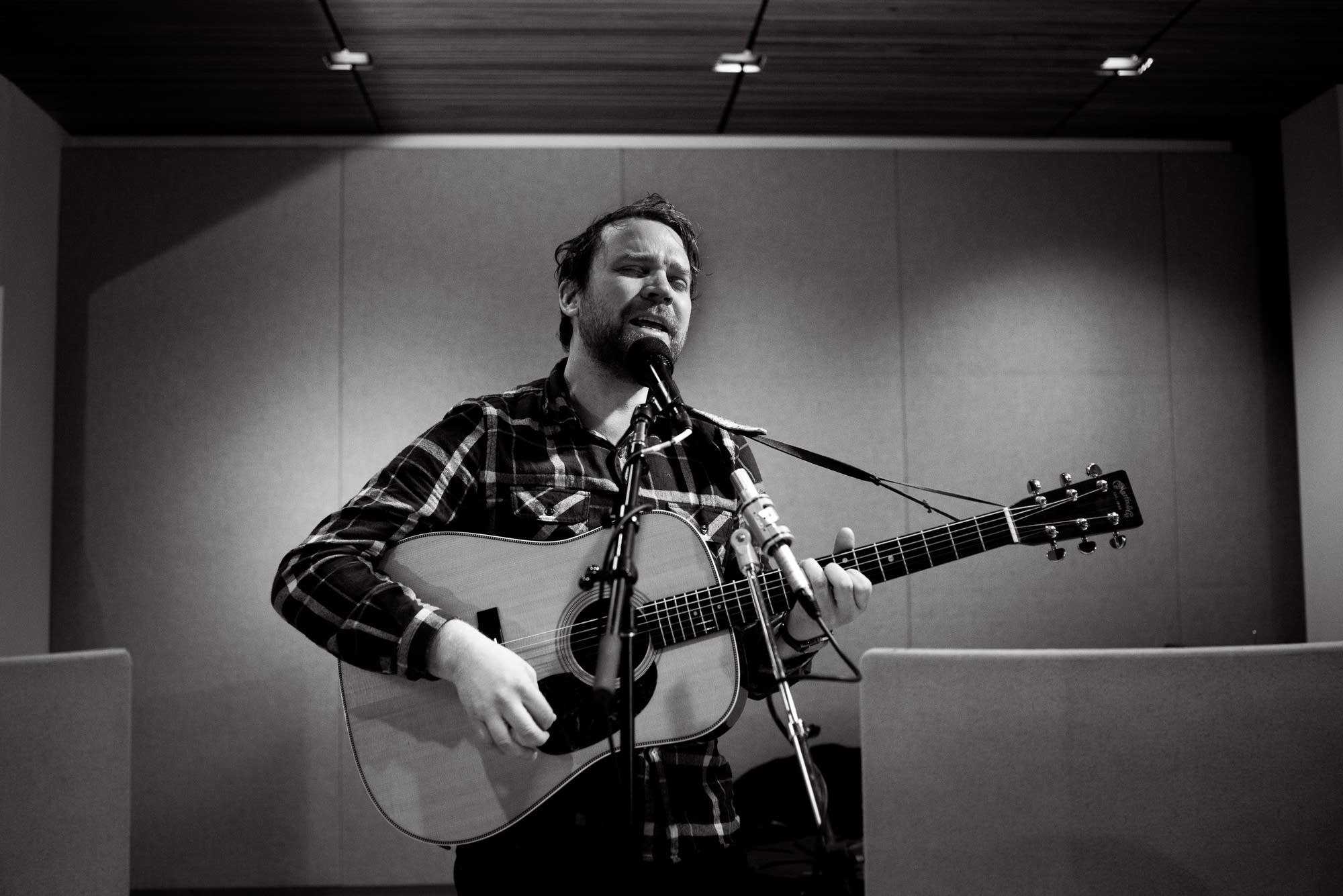

Photo Credit (FR banner): Dan Massie

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is a toll-free number 800-273-TALK (8255). Crisis Text Line offers free help for those who are having a mental health crisis. Text HOME to 741741. Services are available 24/7.

Additional resources are available online here.

Additionally, Tiny Changes, a charity registered in Scotland and created by the Hutchison family offers additional information and support via outreach programs. They are accepting donations of any amount to fund their good work.